Stamping metal jewelry is a meticulous craft that combines artistic expression with technical precision, a practice that has evolved over centuries and remains a cornerstone of jewelry-making today. This process, often referred to as metal stamping or impression stamping, involves the use of tools to imprint designs, letters, or patterns onto metal surfaces, typically for the creation of personalized or decorative jewelry pieces such as pendants, bracelets, rings, and earrings. The technique is celebrated for its versatility, allowing artisans to work with a variety of metals, from soft materials like copper and aluminum to harder alloys like stainless steel. In this expansive exploration, we will delve into the history, materials, tools, techniques, scientific principles, and practical applications of metal stamping in jewelry-making, providing a comprehensive resource that bridges traditional craftsmanship with modern innovation.

The origins of metal stamping can be traced back to ancient civilizations, where early metalworkers used rudimentary tools to mark or decorate metal objects. Archaeological evidence suggests that the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans employed basic stamping techniques to inscribe symbols or ownership marks onto gold, silver, and bronze artifacts. These early methods relied on handheld chisels and hammers, with designs carved into the tools themselves to transfer patterns onto softened metal surfaces. Over time, the Industrial Revolution in the 18th and 19th centuries revolutionized metalworking, introducing mechanical presses and standardized stamps that allowed for greater consistency and efficiency. Today, metal stamping in jewelry-making retains its artisanal roots while incorporating advanced tools and materials, making it accessible to both hobbyists and professional jewelers.

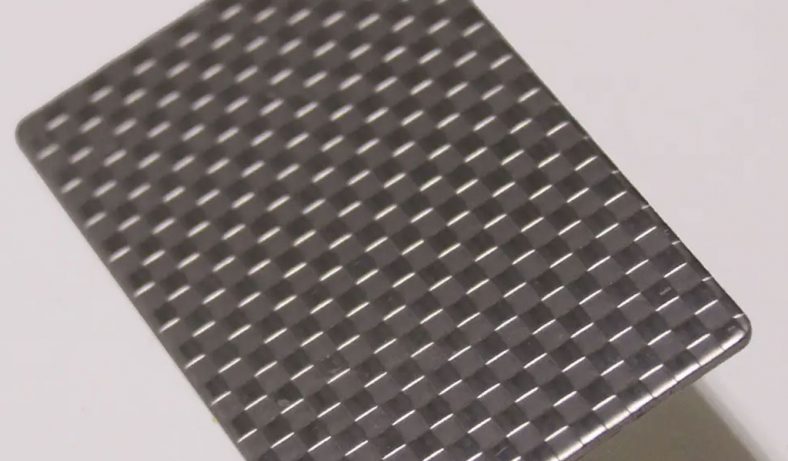

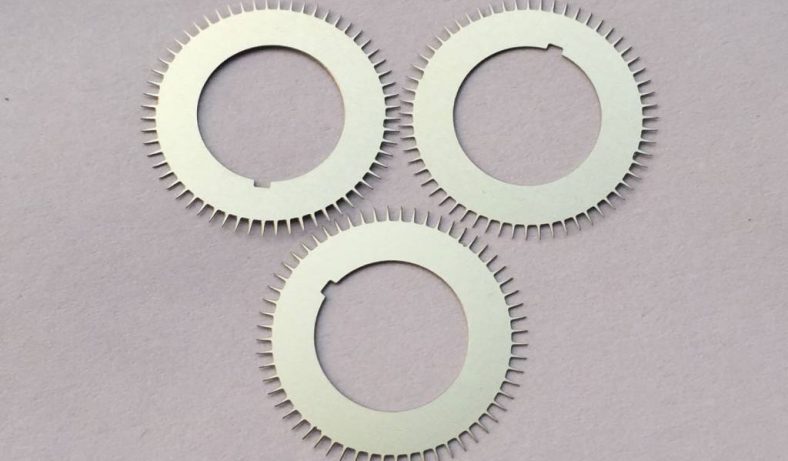

At its core, metal stamping involves the application of force to deform a metal surface, creating a permanent impression. The process requires a combination of a metal blank (the workpiece), a stamp or die (the tool with the desired design), and a striking implement (typically a hammer or press). The metal blank is placed on a stable surface, often a steel bench block, and the stamp is positioned precisely before being struck with controlled force. The result is a recessed design that can range from simple alphanumeric characters to intricate motifs, depending on the stamp used. This seemingly straightforward technique is underpinned by complex material science principles, including ductility, malleability, and work hardening, which dictate how different metals respond to the stamping process.

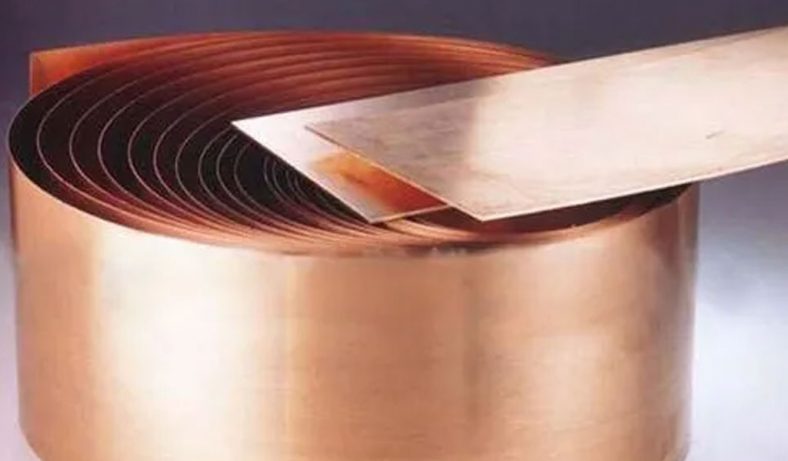

The choice of metal is a critical factor in metal stamping, as each material exhibits unique physical properties that influence the outcome. Common metals used in jewelry stamping include copper, brass, aluminum, silver, gold, and stainless steel, each offering distinct advantages and challenges. Copper, for instance, is a soft, ductile metal with a Mohs hardness of approximately 3, making it easy to stamp with minimal force. Its reddish hue and natural patina also lend an aesthetic appeal to finished pieces. Brass, an alloy of copper and zinc, has a slightly higher hardness (around 3.5–4 on the Mohs scale) and a golden tone, providing a balance between workability and durability. Aluminum, with a hardness of 2.5–3, is lightweight and highly malleable, ideal for beginners or large-scale designs, though it lacks the luster of precious metals. Sterling silver, a popular choice in fine jewelry, has a hardness of 2.5–3 and offers excellent ductility, though its cost and tendency to tarnish require careful handling. Gold, available in various karats (e.g., 14K or 18K), is similarly soft (2.5–3 on the Mohs scale) but is prized for its rarity and resistance to corrosion. Stainless steel, with a hardness of 5.5–6.5, is significantly harder and more resistant to deformation, necessitating specialized tools and greater force.

To illustrate the diversity of these materials, consider the following table, which compares their key properties relevant to metal stamping:

| Metal | Mohs Hardness | Density (g/cm³) | Malleability | Ductility | Corrosion Resistance | Typical Use in Jewelry |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | 3 | 8.96 | High | High | Moderate | Pendants, earrings, practice pieces |

| Brass | 3.5–4 | 8.4–8.7 | Moderate | Moderate | Moderate | Bracelets, decorative elements |

| Aluminum | 2.5–3 | 2.7 | High | High | High | Lightweight pendants, tags |

| Sterling Silver | 2.5–3 | 10.36 | High | High | Low (tarnishes) | Rings, necklaces, fine jewelry |

| Gold (14K) | 2.5–3 | 13.0–15.0 | High | High | High | Luxury rings, pendants |

| Stainless Steel | 5.5–6.5 | 7.8–8.0 | Low | Low | Very High | Durable tags, industrial designs |

These properties directly affect the stamping process. Softer metals like copper and aluminum require less force to imprint, making them forgiving for novices, while harder metals like stainless steel demand precision and robust equipment. The malleability of a metal, or its ability to deform under pressure without cracking, determines how deeply a stamp can penetrate before the material resists further deformation. Ductility, the capacity to stretch without breaking, is less critical in stamping but influences how the metal behaves if additional forming (e.g., bending or doming) is applied post-stamping. Corrosion resistance, meanwhile, impacts the longevity and maintenance of the finished jewelry piece.

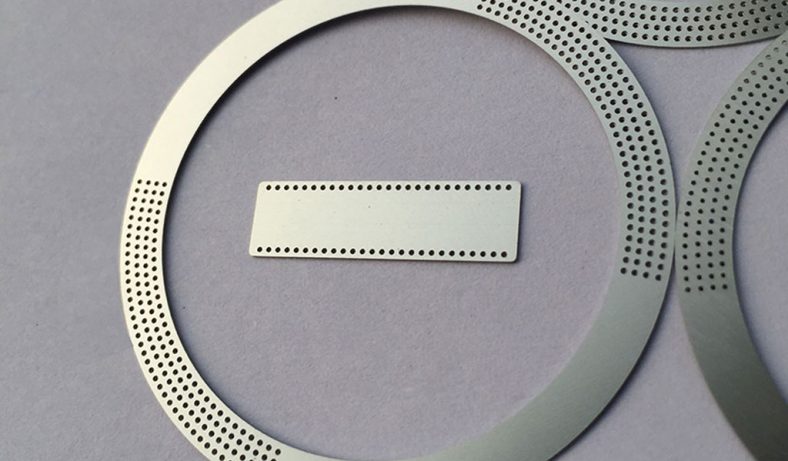

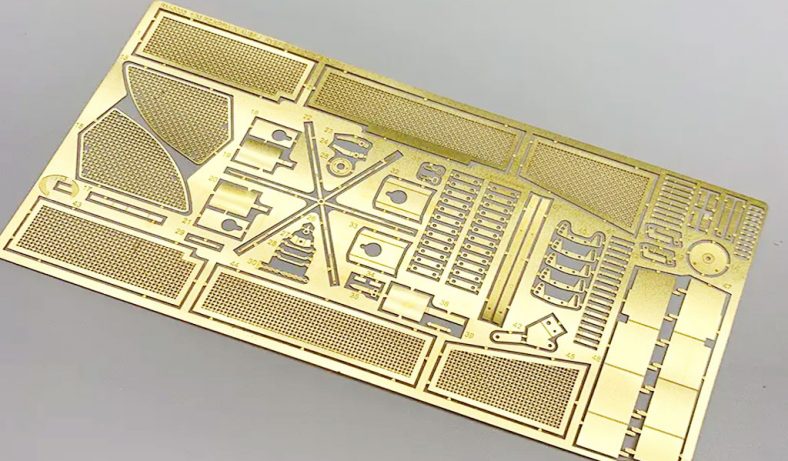

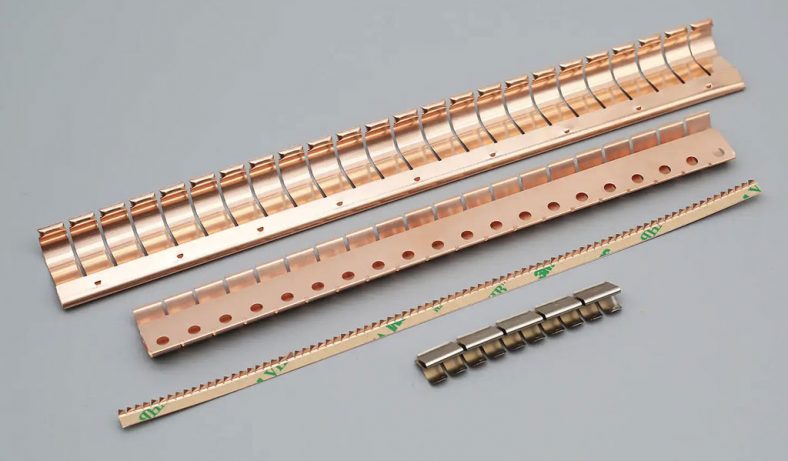

The tools of metal stamping are equally diverse, ranging from basic hand tools to advanced machinery. The most essential tool is the metal stamp itself, typically made from hardened steel to withstand repeated striking without deforming. Stamps come in various forms, including letter sets (for monograms or words), number sets, and decorative designs (e.g., stars, hearts, or florals). These are often sold in kits, with font sizes ranging from 1.5 mm to 6 mm or larger, catering to different project scales. A steel bench block serves as the stamping surface, providing a hard, flat foundation that absorbs impact and prevents the metal blank from bending. Hammers are the traditional striking tool, with options like the chasing hammer (featuring a broad, flat face and a narrow, rounded end) or the ball-peen hammer (with a domed striking surface) offering versatility in force application. For greater precision and consistency, mechanical presses—manual or pneumatic—can replace hammers, delivering uniform pressure across larger or harder surfaces.

The physics of metal stamping hinges on the transfer of kinetic energy from the hammer or press to the stamp, which then deforms the metal blank. When a hammer strikes a stamp, the force (F) applied is governed by Newton’s second law, F = ma, where m is the mass of the hammerhead and a is its acceleration upon impact. The energy transferred, measured in joules, depends on the hammer’s mass and velocity: E = ½mv². For a typical 1-pound (0.45 kg) hammer swung at 5 m/s, the kinetic energy is approximately 5.625 joules, sufficient to deform soft metals like copper or silver. Harder metals, however, may require energies exceeding 10–15 joules, achievable with heavier hammers or presses. The stamp’s design also plays a role: a finely detailed stamp with a small surface area concentrates force (pressure = force/area), penetrating deeper, while a broad stamp distributes force, creating shallower impressions.

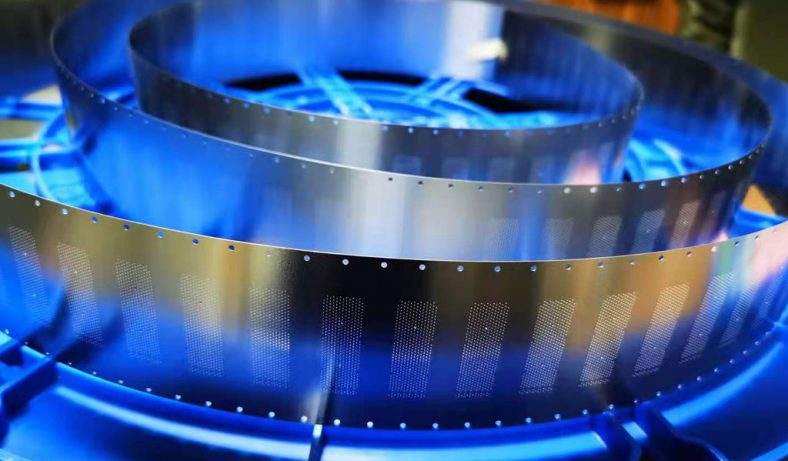

Work hardening, a metallurgical phenomenon, further complicates the process. As a metal is struck, its crystalline structure compresses, increasing its hardness and resistance to further deformation. This is quantified by the metal’s yield strength, which rises with each impact. For example, annealed copper has a yield strength of approximately 50 MPa, but after stamping, this can increase to 200 MPa or more, depending on the degree of deformation. This hardening enhances durability but can make subsequent stamps less effective unless the metal is annealed—heated and cooled to restore its softness. Annealing temperatures vary by metal: copper requires 400–600°C, silver 600–650°C, and stainless steel 800–1000°C, each followed by controlled cooling to prevent brittleness.

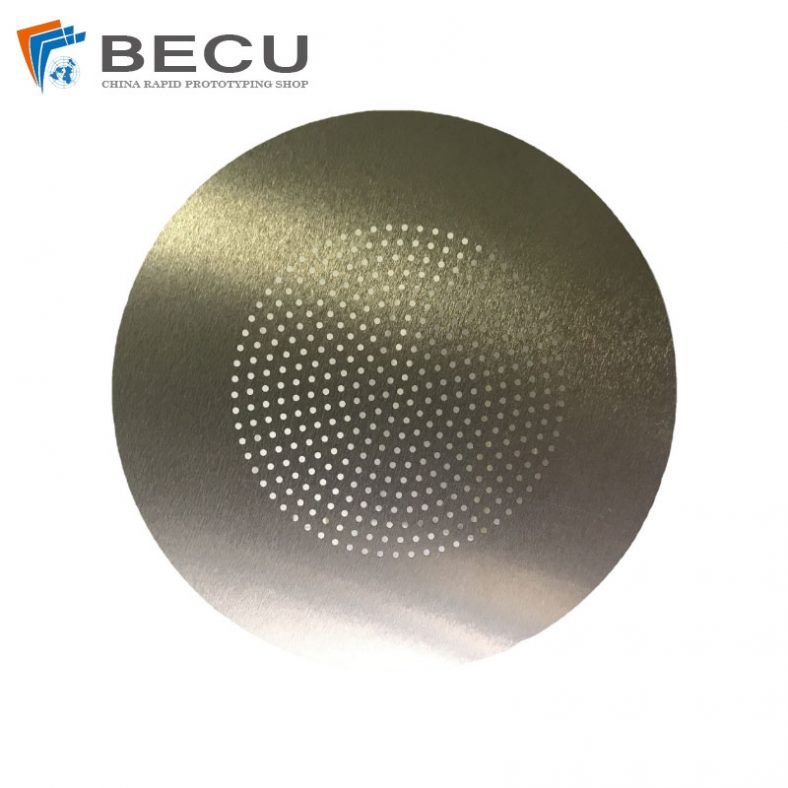

The technique of stamping metal jewelry begins with preparation. The metal blank—often a pre-cut disc, square, or custom shape—is cleaned to remove oils or debris, ensuring a smooth surface for stamping. For softer metals, a single strike may suffice, but harder metals may require multiple blows, each carefully aligned to avoid double impressions. Alignment is critical, especially for text: jewelers often use painter’s tape or a stamping jig to secure the blank and guide the stamp, ensuring even spacing and straight lines. The angle of the stamp matters too—holding it perpendicular to the surface maximizes force transfer, while angling it risks uneven impressions or stamp damage.

Post-stamping, the piece is refined. Excess burrs or rough edges are filed or sanded, and the stamped design can be enhanced with oxidation (using liver of sulfur to darken recesses) or polishing (to highlight raised areas). Additional embellishments, such as gemstone settings or enamel, may be added, though these require compatibility with the stamped metal’s properties. For instance, soldering components onto stamped silver requires a lower melting point solder (e.g., 650°C) to avoid damaging the base metal.

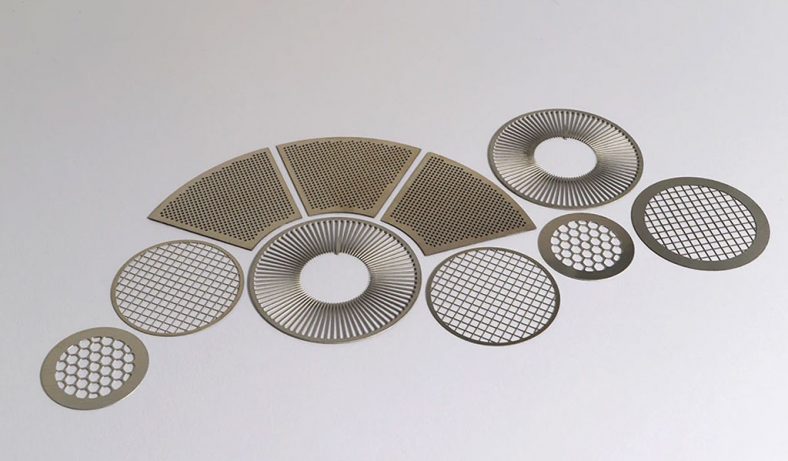

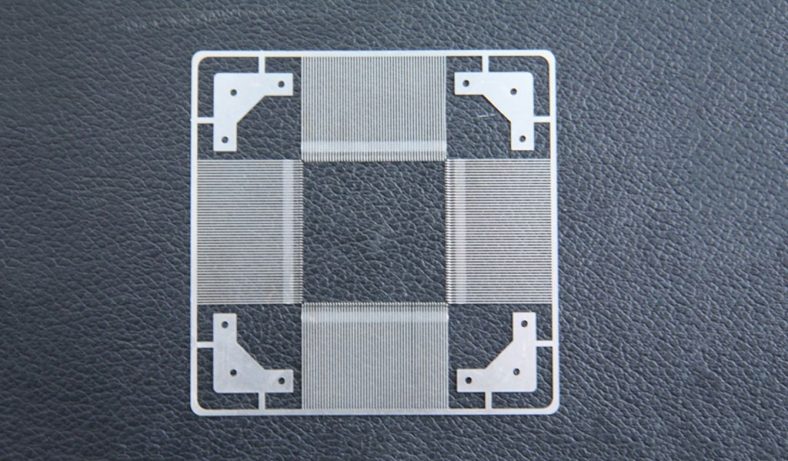

The scientific precision of metal stamping extends to its repeatability. In mass production, jewelry manufacturers use hydraulic presses with custom dies, capable of exerting forces up to 100 tons or more, to stamp thousands of identical pieces. These machines operate on Pascal’s principle, where pressure applied to a confined fluid is transmitted equally in all directions, ensuring consistent impressions across large batches. Hand stamping, by contrast, retains an artisanal charm, with slight variations in pressure or alignment lending each piece a unique character.

Safety is paramount in metal stamping, given the forces and tools involved. Eye protection guards against flying debris, while gloves prevent burns during annealing or cuts from sharp edges. Proper ventilation is essential when using chemicals like patinas or when heating metals, as fumes can be hazardous. Beginners are advised to start with soft metals and basic tools, gradually scaling up to harder materials and complex designs as skill develops.

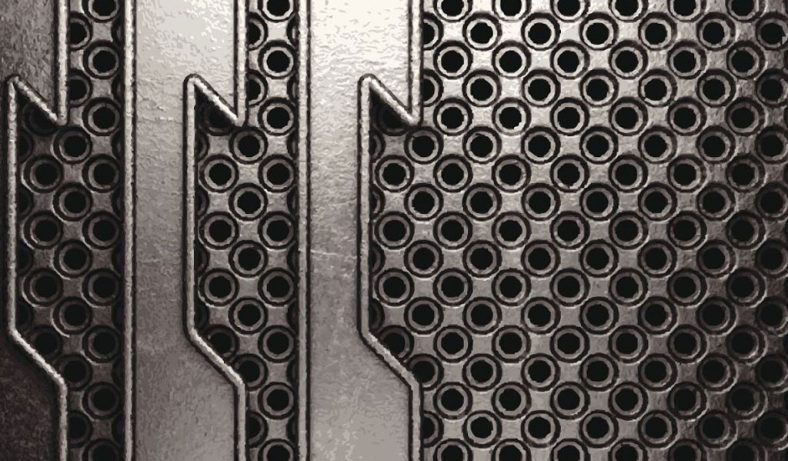

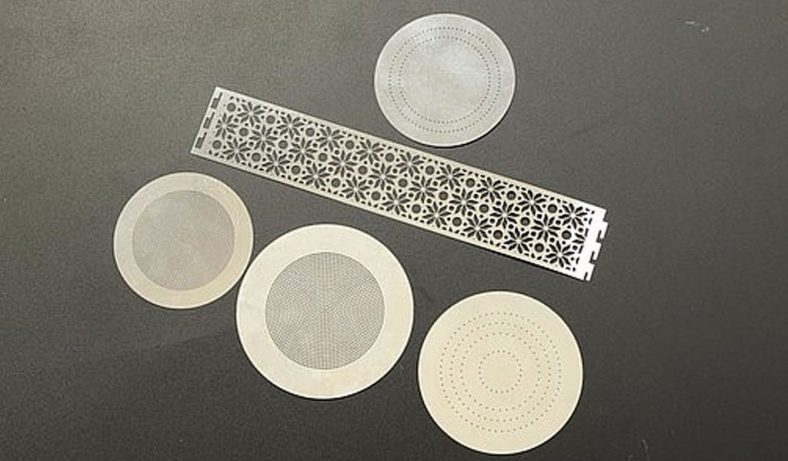

The applications of metal stamping in jewelry are vast. Personalized items—name necklaces, initialed rings, or date-stamped bracelets—dominate the craft, appealing to sentimental buyers. Decorative stamping, such as floral or geometric patterns, adds texture to minimalist designs, while mixed-media pieces combine stamped metal with leather, wood, or resin for eclectic aesthetics. Commercially, stamped jewelry ranges from affordable aluminum tags to high-end gold pendants, with prices reflecting material costs and craftsmanship.

To expand on the practical nuances, consider the following table of stamping techniques and their outcomes:

| Technique | Tool Used | Force Required | Metal Suitability | Resulting Effect | Common Issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Single Strike | Hammer, stamp | Low–Moderate | Copper, aluminum, silver | Shallow, crisp impression | Misalignment, faint marks |

| Multiple Strikes | Hammer, stamp | Moderate–High | Brass, stainless steel | Deep, bold impression | Double impressions, warping |

| Press Stamping | Manual/pneumatic press | High | All metals | Uniform, repeatable design | Equipment cost, setup time |

| Textured Stamping | Patterned stamp | Moderate | Soft–medium metals | Broad, decorative texture | Uneven depth, stamp wear |

| Annealed Stamping | Hammer, stamp (post-anneal) | Low | Work-hardened metals | Restored softness, deep marks | Heat discoloration, warping |

This table underscores the adaptability of metal stamping, accommodating diverse artistic goals and technical constraints. Single-strike stamping suits quick, simple projects, while multiple strikes or presses tackle robust materials. Textured stamping, often overlooked, adds visual complexity, though it demands stamps with durable, broad designs to avoid premature wear.

The cultural significance of stamped jewelry cannot be overstated. In ancient times, stamped seals or amulets bore protective symbols or royal insignia, linking the craft to identity and power. Today, it serves both functional and expressive purposes, from dog tags to wedding bands. Its accessibility—requiring minimal startup costs (a basic kit of stamps, hammer, and block costs under $50)—has fueled its popularity among DIY enthusiasts, while its scalability supports professional studios producing bespoke or mass-market pieces.

In conclusion, stamping metal jewelry is a multifaceted discipline that marries art, science, and history. Its reliance on material properties, force dynamics, and tool design invites endless experimentation, while its tactile, hands-on nature preserves a connection to traditional craftsmanship. Whether pursued as a hobby or a profession, metal stamping offers a gateway to creating durable, meaningful adornments, each impression a testament to the maker’s skill and vision. As technology advances, integrating laser-guided stamps or 3D-printed dies, the craft continues to evolve, yet its essence—transforming metal through deliberate force—remains timeless.