Etching, a technique rooted in both artistic expression and scientific precision, has captivated creators and researchers for centuries. This intricate process involves the selective removal of material from a surface—typically metal, glass, or stone—using chemical or physical means to create detailed patterns, designs, or functional textures. From its historical origins in armor decoration to its modern applications in microelectronics and fine art, etching represents a fascinating intersection of creativity and technology. This article explores the vast domain of etching patterns, delving into their sources of inspiration, the diverse techniques employed, and the scientific principles that underpin them. Through an extensive examination of methods, materials, and cultural contexts, we aim to provide a comprehensive resource for understanding this multifaceted craft.

Historical Foundations of Etching

The practice of etching traces its origins to the Middle Ages, when artisans in Europe and the Middle East began using acidic substances to engrave designs onto metal surfaces. One of the earliest known applications emerged in the 15th century, as armorers sought to embellish suits of armor with intricate motifs. These early practitioners applied a mixture of vinegar, salt, and charcoal to copper or iron plates, allowing the acid to corrode the exposed areas and leave behind shallow grooves. The resulting patterns were often inspired by heraldry, nature, or religious iconography, reflecting the cultural priorities of the time.

By the 16th century, etching had evolved into a prominent artistic medium, largely due to the influence of printmakers such as Albrecht Dürer and Daniel Hopfer. Hopfer, a German craftsman, is credited with adapting the technique for printmaking by coating iron plates with a wax resist, scratching designs into the wax, and then immersing the plate in acid. This innovation allowed for the mass production of detailed images, democratizing art and enabling the dissemination of knowledge during the Renaissance. The patterns etched during this period often drew inspiration from classical mythology, landscapes, and human portraiture, showcasing the versatility of the medium.

As etching spread across Europe, regional styles emerged. Italian artists favored elaborate, swirling designs inspired by the Baroque aesthetic, while Dutch printmakers like Rembrandt van Rijn explored moody, atmospheric compositions with fine cross-hatching. These historical developments laid the groundwork for the diverse array of etching techniques and patterns seen today, blending artistic ingenuity with technical mastery.

Scientific Principles of Etching

At its core, etching relies on the controlled removal of material through chemical or physical processes. The most common method, chemical etching, involves the use of an etchant—a corrosive substance such as an acid or base—that reacts with the substrate to dissolve unprotected areas. The choice of etchant depends on the material being etched: hydrochloric acid is frequently used for copper, while hydrofluoric acid is employed for glass. The reaction can be represented by a general chemical equation:

M+nHA→MAn+2nH2

where M M M is the metal substrate, HA HA HA is the acid, and MAn MA_n MAn is the resulting metal salt, with hydrogen gas (H2 H_2 H2) as a byproduct. This process is highly selective, as a resist material—such as wax, photoresist, or polymer—protects designated areas from the etchant, preserving the desired pattern.

Physical etching, by contrast, involves the mechanical removal of material through abrasion, ion bombardment, or laser ablation. In reactive ion etching (RIE), a plasma of charged particles bombards the surface, dislodging atoms in a controlled manner. The precision of physical etching makes it indispensable in modern semiconductor manufacturing, where nanoscale patterns are critical to the performance of integrated circuits.

The interplay between chemical and physical mechanisms allows for a wide range of pattern complexities, from broad, shallow designs to intricate, high-resolution features. Factors such as etchant concentration, exposure time, temperature, and substrate composition all influence the final outcome, requiring practitioners to balance empirical knowledge with theoretical understanding.

Sources of Inspiration for Etching Patterns

Etching patterns draw inspiration from an expansive array of sources, spanning nature, culture, mathematics, and technology. Each influence contributes unique aesthetic and functional qualities, shaping the evolution of the craft.

Nature as a Muse

Natural forms have long served as a wellspring of inspiration for etchers. The organic symmetry of leaves, the fractal branching of trees, and the hexagonal tessellation of honeycombs offer endless possibilities for pattern design. For example, botanical illustrations etched onto copper plates in the 18th century captured the delicate veins of foliage with remarkable fidelity, blending scientific observation with artistic interpretation. Similarly, the swirling patterns of ocean waves or the crystalline structure of snowflakes have inspired abstract designs that evoke movement and texture.

In contemporary practice, biomimicry—the imitation of natural systems—has gained prominence. Etchers replicate the microtextures of shark skin or lotus leaves, which exhibit water-repellent properties due to their nanoscale roughness. These patterns, achieved through advanced techniques like laser etching, demonstrate how nature’s efficiency can inform both decorative and utilitarian applications.

Cultural and Historical Influences

Cultural traditions provide another rich vein of inspiration. Islamic art, with its emphasis on geometric abstraction and arabesque motifs, has influenced etching patterns across centuries. Artisans in the Middle East historically etched brass and silver with interlocking stars and floral scrolls, a practice that continues in modern metalwork. Similarly, East Asian calligraphy and ink wash painting have inspired etched designs on porcelain and glass, characterized by fluid brushstroke-like patterns.

In the Western tradition, the Gothic Revival of the 19th century spurred a resurgence of medieval-inspired etchings, featuring pointed arches, gargoyles, and stained-glass motifs. These culturally rooted patterns often carry symbolic weight, reflecting the values and narratives of their time.

Mathematical and Geometric Precision

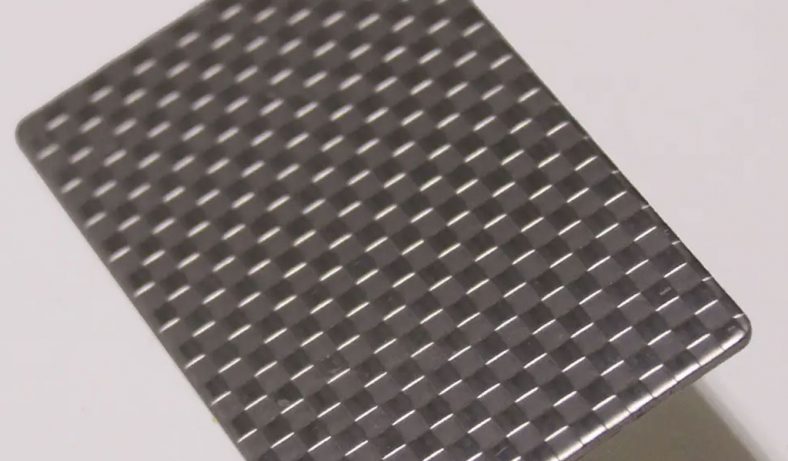

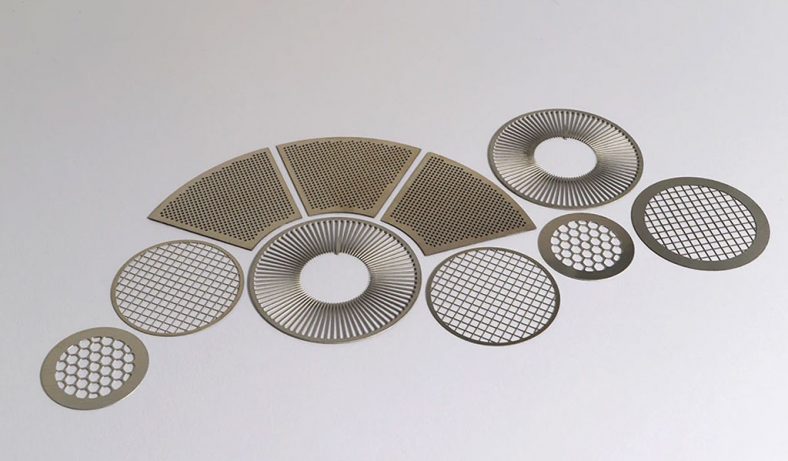

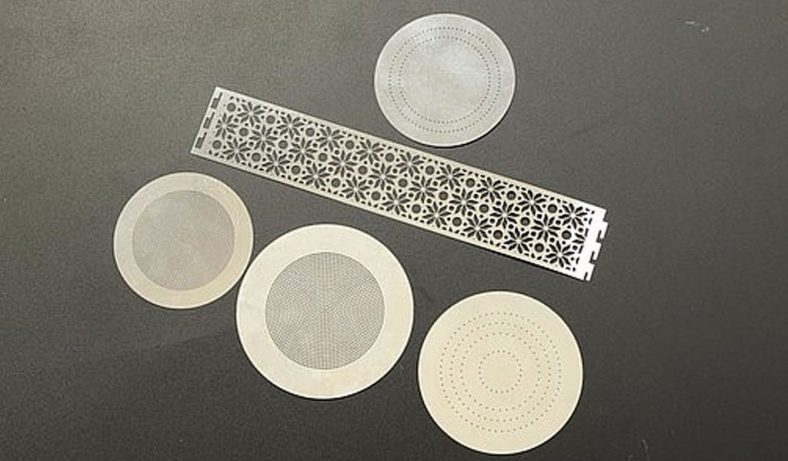

Mathematics offers a framework for creating patterns of striking order and complexity. Tessellations—repeating shapes that tile a surface without gaps—underlie many etched designs, from simple grids to elaborate Penrose tilings. The Fibonacci sequence and golden ratio, which govern proportions in nature, have also been translated into spiral and radial patterns, lending a sense of harmony to the work.

Fractal geometry, with its self-similar structures, has become particularly influential in modern etching. Using computer-aided design (CAD) software, artists and engineers generate fractal patterns that are then etched onto surfaces with micron-scale precision. These designs, often resembling coastlines or fern leaves, bridge the gap between abstract mathematics and tangible form.

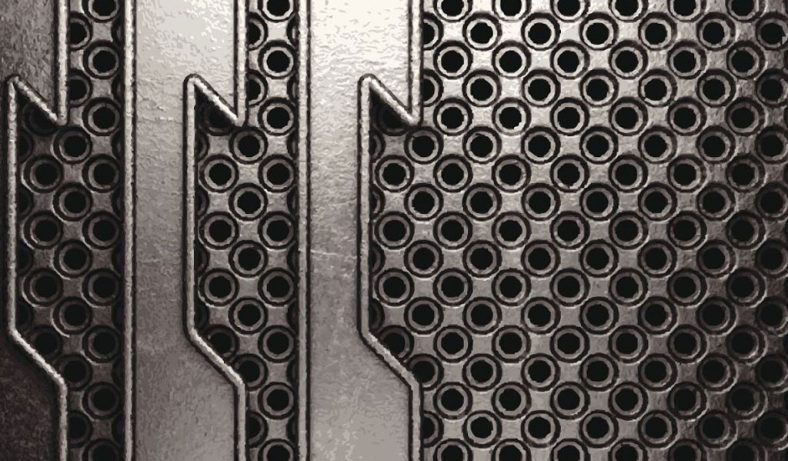

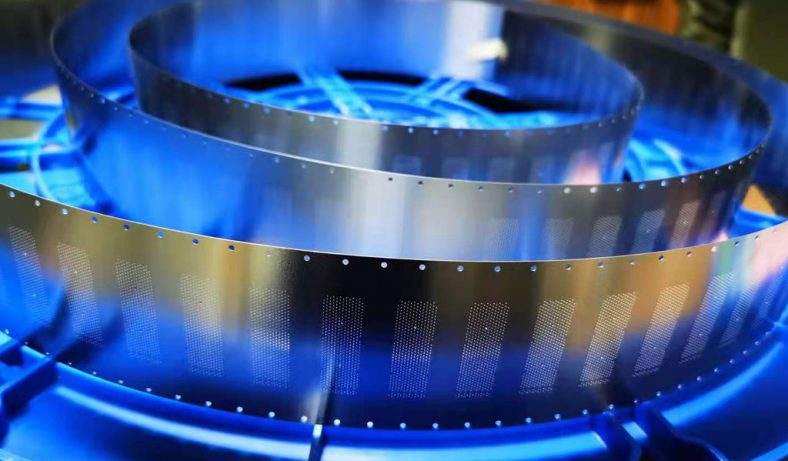

Technological and Industrial Aesthetics

The rise of industrialization and digital technology has introduced new inspirations drawn from machinery, circuitry, and data visualization. Etched patterns on microchips, for instance, mimic the angular, grid-like layouts of urban landscapes or electrical networks. Steampunk artists have embraced this aesthetic, etching brass and steel with gear-like motifs and Victorian flourishes.

In experimental art, data-driven patterns—such as those derived from sound waves, weather patterns, or genetic sequences—offer a novel approach. Etchers translate these abstract datasets into visual forms, creating works that are both conceptually rich and visually compelling.

Techniques of Etching

Etching encompasses a diverse suite of techniques, each suited to specific materials, scales, and artistic goals. Below, we explore the primary methods, their processes, and their applications, accompanied by detailed comparisons.

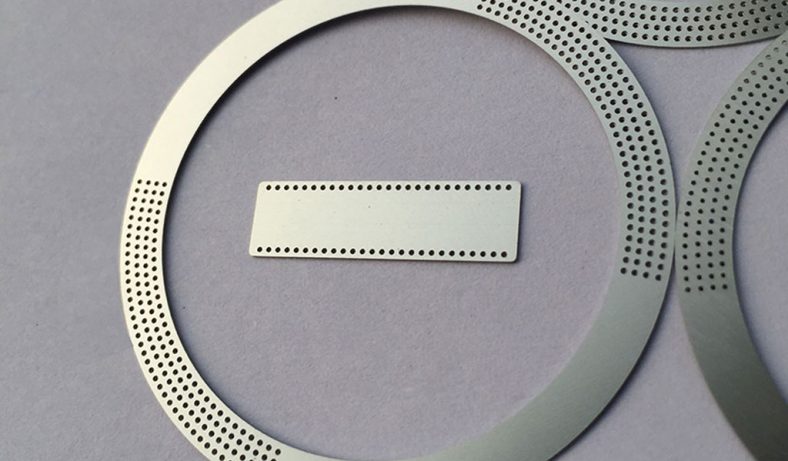

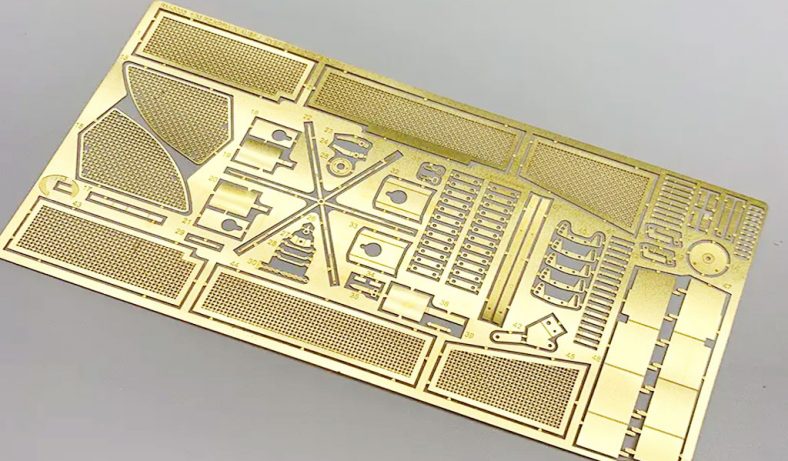

Traditional Chemical Etching

Traditional chemical etching, also known as wet etching, remains a cornerstone of the craft. The process begins with the preparation of the substrate, which is cleaned and coated with a resist. The resist is then selectively removed—by hand, using a stylus, or via photographic exposure—to expose the areas to be etched. The substrate is submerged in an etchant bath, where the chemical reaction erodes the unprotected material. After a set time, the plate is neutralized, and the resist is stripped away, revealing the pattern.

This technique excels in creating fine, shallow designs on metals like copper, zinc, and steel. Its simplicity and low cost make it accessible to artists, though it lacks the precision of modern methods for submicron features. Common etchants include ferric chloride for copper and nitric acid for zinc, each chosen for its reactivity and safety profile.

Photoetching

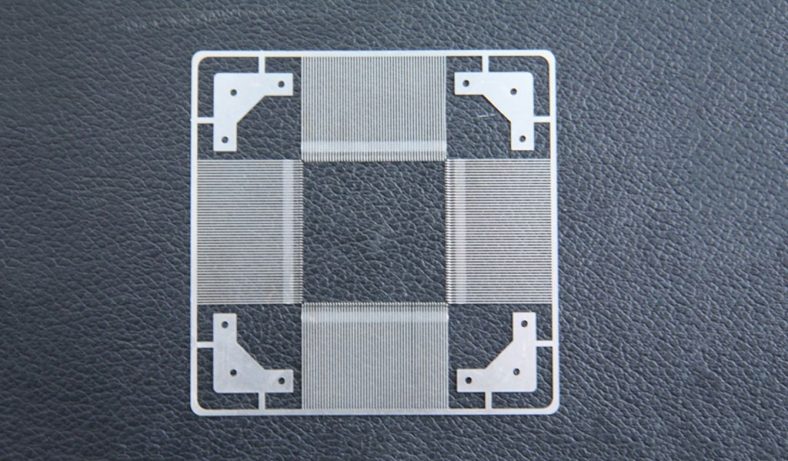

Photoetching, or photolithography, emerged in the 19th century and gained prominence in industrial applications. A photosensitive resist is applied to the substrate and exposed to ultraviolet light through a patterned mask. The exposed areas harden (or soften, depending on the resist type), and the unexposed areas are washed away, leaving a stencil for etching. This method is widely used in electronics to fabricate printed circuit boards and microchips, where patterns must be accurate to nanometers.

Photoetching offers unmatched resolution and repeatability, making it ideal for mass production. However, it requires specialized equipment, such as UV exposure units and cleanroom facilities, limiting its use in small-scale art studios.

Dry Etching

Dry etching encompasses techniques that use gases or plasmas rather than liquid etchants. Reactive ion etching (RIE), a subset of dry etching, employs a vacuum chamber filled with a reactive gas (e.g., sulfur hexafluoride). An electric field ionizes the gas, creating a plasma that bombards the substrate and etches it anisotropically—meaning it removes material vertically rather than laterally. This directional precision is critical for deep, narrow patterns in semiconductor manufacturing.

Other dry methods include sputter etching, which uses inert ions like argon, and vapor-phase etching, which employs gaseous etchants like xenon difluoride. These techniques are highly controlled but demand sophisticated machinery, restricting their use to industrial and research settings.

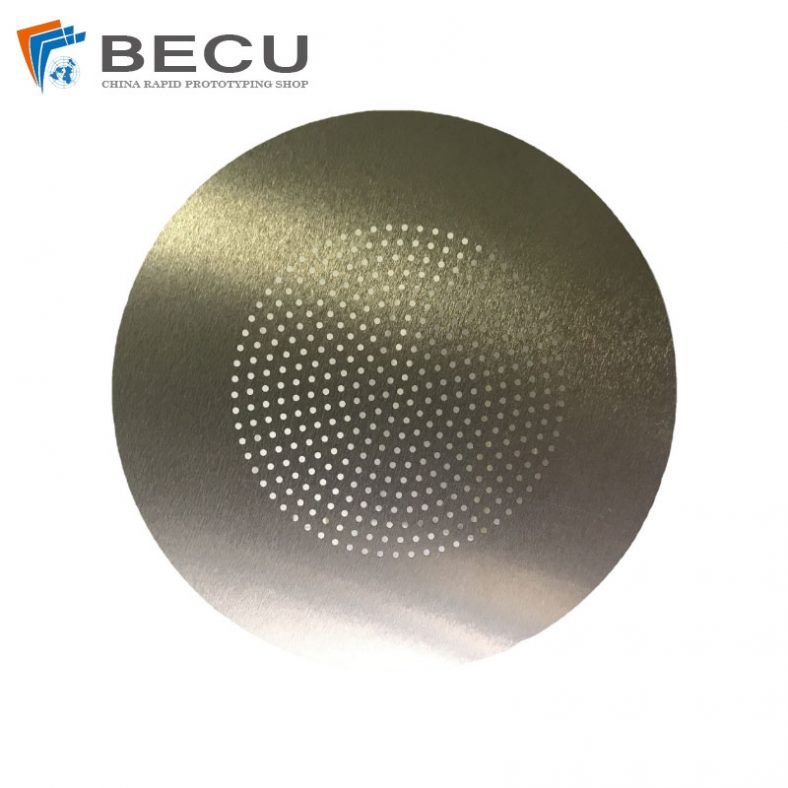

Laser Etching

Laser etching uses focused beams of light to vaporize or ablate material from a surface. The laser’s intensity, wavelength, and pulse duration can be adjusted to achieve varying depths and resolutions, from broad cuts to microscopic details. Materials like wood, glass, metal, and polymers are all compatible, making laser etching exceptionally versatile.

This technique is prized for its speed and precision, as well as its ability to produce complex patterns without physical contact. Artists use it to replicate hand-drawn designs, while industries employ it for serial numbers and branding. However, the high cost of laser systems and the need for digital design skills can be barriers to entry.

Mechanical Etching

Mechanical etching, or engraving, involves the direct removal of material using tools like burins, routers, or abrasive particles. While less common in modern chemical-dominated etching, it remains relevant in jewelry making and intaglio printing. The tactile nature of mechanical etching allows for unique textures, such as stippling or cross-hatching, that chemical methods cannot replicate.

This method is labor-intensive and less suited to large-scale production, but its handcrafted quality appeals to artisans seeking a traditional aesthetic.

Comparative Analysis of Etching Techniques

To elucidate the strengths and limitations of each method, the following table provides a detailed comparison across key parameters:

| Technique | Materials | Resolution | Depth Control | Speed | Cost | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Etching | Metals, glass | Moderate (µm) | Shallow to moderate | Slow | Low | Art, printmaking, basic circuitry |

| Photoetching | Metals, semiconductors | High (nm) | Shallow to moderate | Moderate | High | Microelectronics, PCBs |

| Reactive Ion Etching | Semiconductors, metals | Very high (nm) | High | Moderate | Very high | IC fabrication, MEMS |

| Laser Etching | Metals, glass, polymers | High (µm to nm) | High | Fast | Moderate to high | Art, industrial marking, prototyping |

| Mechanical Etching | Metals, stone, wood | Low to moderate (µm) | High | Very slow | Low to moderate | Jewelry, intaglio, decorative work |

This table underscores the trade-offs between precision, cost, and scalability, guiding practitioners in selecting the appropriate technique for their needs.

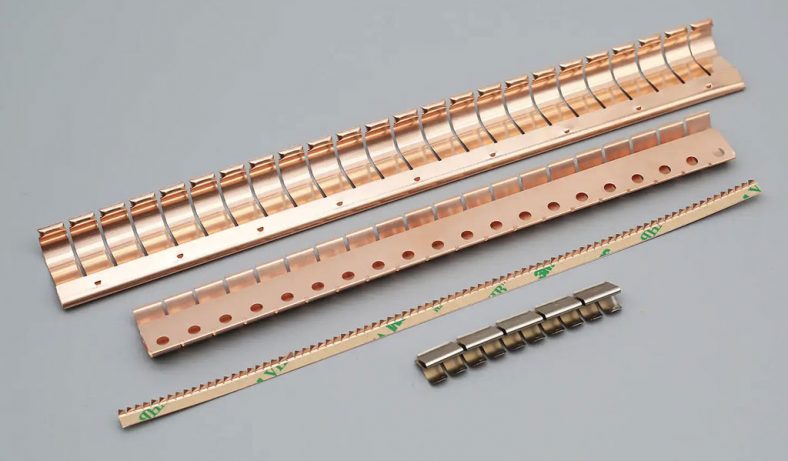

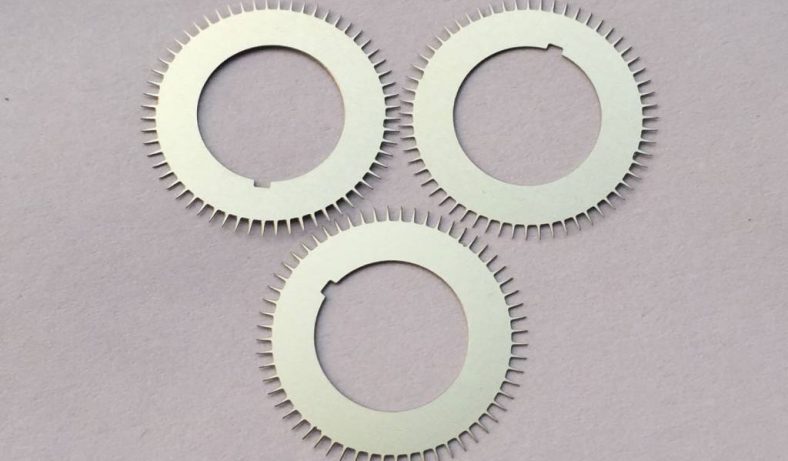

Materials and Substrates

The choice of substrate profoundly affects the etching process and the resulting pattern. Metals like copper, brass, and stainless steel are favored for their durability and reactivity with common etchants. Glass, prized for its transparency and smoothness, requires hydrofluoric acid or abrasive blasting due to its chemical inertness. Polymers, such as acrylic and polycarbonate, are increasingly popular in laser etching for their flexibility and low cost.

Ceramics and semiconductors, like silicon and gallium arsenide, dominate high-tech applications. Silicon’s crystalline structure allows for anisotropic etching, where the etchant follows specific crystallographic planes, yielding sharp, predictable patterns. The table below compares common substrates:

| Substrate | Etchant | Pattern Characteristics | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Copper | Ferric chloride | Fine, shallow grooves | Printmaking, circuitry |

| Glass | Hydrofluoric acid | Smooth, frosted textures | Decorative glass, optics |

| Silicon | Potassium hydroxide | Sharp, anisotropic features | Microchips, sensors |

| Stainless Steel | Nitric acid | Durable, moderate depth | Industrial parts, art |

| Acrylic | Laser ablation | Clean, variable depth | Signage, prototypes |

Modern Innovations and Applications

Etching has transcended its traditional boundaries, finding applications in cutting-edge fields. In nanotechnology, electron beam lithography etches patterns smaller than 10 nanometers, enabling the development of quantum devices. In medicine, etched titanium implants mimic bone structure, enhancing biocompatibility. Even in space exploration, etched metal plates on spacecraft withstand harsh conditions while displaying critical information.

Artists, too, have embraced innovation. Digital tools like CAD and 3D modeling software allow for the creation of multilayered patterns, which are then etched onto substrates using hybrid techniques. The fusion of traditional craftsmanship with modern technology ensures that etching remains a vibrant and evolving discipline.

Cultural and Artistic Significance

Beyond its technical aspects, etching holds profound cultural value. It has preserved historical narratives, from the maps of early explorers to the satirical prints of the Enlightenment. Today, it continues to serve as a medium for expression, with artists like Kiki Smith and Julie Mehretu using etching to explore identity, memory, and abstraction.

The patterns themselves—whether geometric, organic, or symbolic—carry meaning. They connect humanity to its past, its environment, and its imagination, making etching a bridge between the tangible and the conceptual.

Conclusion

Etching patterns represent a remarkable synthesis of inspiration and technique, drawing from nature, culture, and science to create works of enduring beauty and utility. From the acid-bitten plates of the Renaissance to the plasma-etched wafers of the digital age, this craft has adapted to the needs and visions of each era. By understanding its historical roots, scientific foundations, and modern innovations, we can appreciate the depth and diversity of etching as both an art form and a technology. As practitioners continue to push its boundaries, etching promises to remain a vital tool for creativity and discovery.