Etching depth control is a critical aspect of materials science and engineering, underpinning the precision fabrication of components across diverse industries, from microelectronics to aerospace. Etching, the process of selectively removing material from a substrate using chemical, physical, or combined means, requires meticulous management of depth to achieve desired geometries, surface properties, and functional outcomes. Whether employing wet chemical etching, dry plasma etching, or advanced laser-based techniques, controlling etching depth involves balancing multiple parameters—etchant chemistry, exposure time, temperature, substrate properties, and process monitoring. This article delves into the scientific principles, methodologies, and technologies for controlling etching depth, offering an exhaustive examination supplemented by comparative tables to elucidate key differences and applications.

Etching depth, defined as the vertical distance of material removed from the surface, varies from nanometers in semiconductor fabrication to millimeters in metal sculpting. Its control is paramount because deviations can compromise component functionality, such as altering electrical conductivity in circuits or weakening structural integrity in mechanical parts. Historically, etching emerged as an artisanal technique in printmaking, using acids to incise designs into metal plates. Today, it has evolved into a sophisticated science, leveraging advanced instrumentation and real-time monitoring to achieve submicron precision. The ability to control etching depth distinguishes modern manufacturing from its predecessors, enabling innovations like integrated circuits, microfluidic devices, and high-performance alloys.

Fundamental Principles of Etching Depth Control

The control of etching depth hinges on understanding the kinetics and thermodynamics of material removal. In wet chemical etching, an etchant reacts with the substrate, dissolving material at a rate governed by the reaction’s activation energy, concentration, and temperature. The depth of material removed can be expressed as:

d=R×t

where d d d is the etching depth, R R R is the etch rate (typically in μm/min), and t t t is the exposure time. The etch rate R R R depends on factors such as etchant molarity, substrate composition, and agitation. For instance, hydrofluoric acid (HF) etches silicon dioxide (SiO₂) at a rate proportional to its concentration, typically ranging from 10 nm/min to 1 μm/min under standard conditions (25°C, 1 M HF). Controlling depth requires precise timing, often achieved with automated timers or endpoint detection systems.

Dry etching, including reactive ion etching (RIE) and plasma etching, introduces additional complexity. Here, depth control relies on ion bombardment and chemical reactions within a plasma environment. The etch rate is influenced by plasma power, gas composition (e.g., CF₄, O₂), and chamber pressure. For example, in RIE of silicon, a mixture of SF₆ and O₂ can achieve etch rates of 0.5–2 μm/min, with depth modulated by adjusting radiofrequency (RF) power (50–500 W). Unlike wet etching, dry processes offer anisotropic profiles, meaning material removal is directional, enhancing depth precision for high-aspect-ratio features.

Laser etching, a non-contact method, controls depth through pulse energy, duration, and repetition rate. A femtosecond laser, for instance, ablates material with minimal thermal diffusion, achieving depths as shallow as 10 nm per pulse in metals like steel. Depth control is refined by calibrating the number of pulses, with each pulse removing a predictable layer based on the material’s ablation threshold (e.g., ~0.1 J/cm² for aluminum).

Wet Chemical Etching: Mechanisms and Depth Control

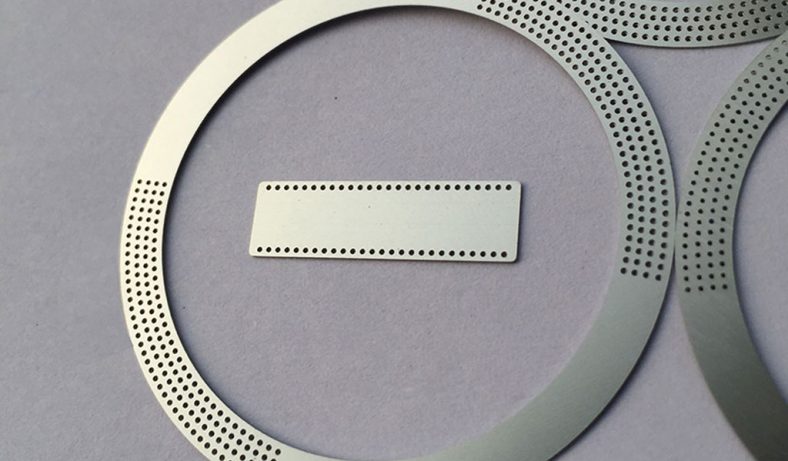

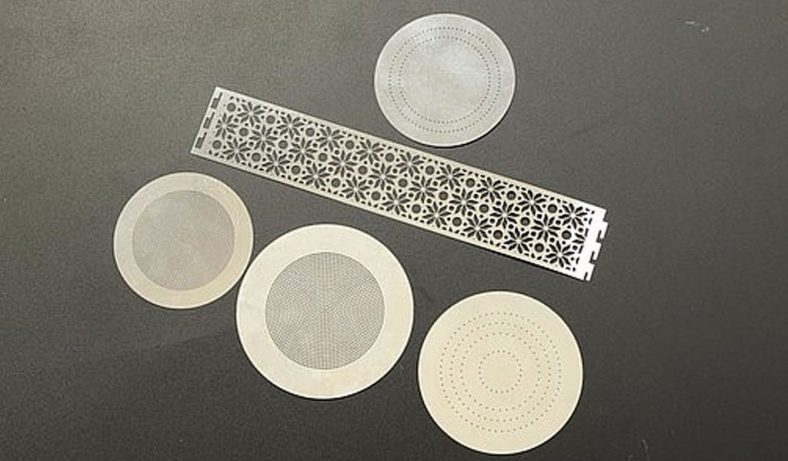

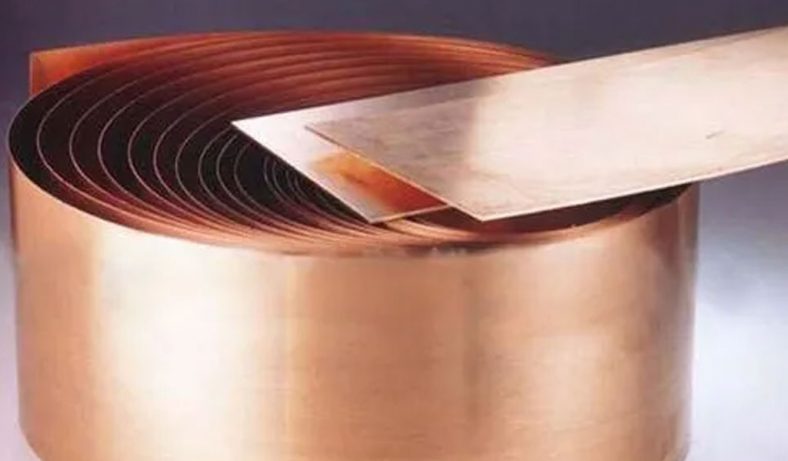

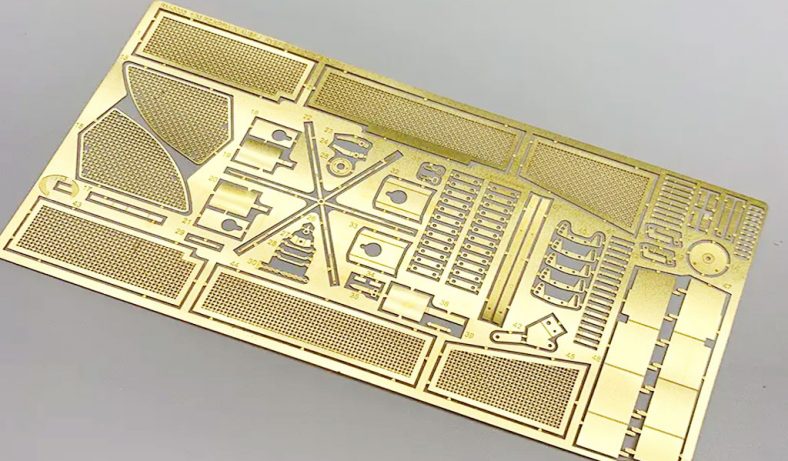

Wet chemical etching remains a cornerstone of industrial processes due to its simplicity and cost-effectiveness. The process involves immersing a masked substrate in an etchant solution, where unprotected areas are selectively dissolved. Depth control in this method depends on several variables:

- Etchant Selection and Concentration: The choice of etchant determines the reaction rate and selectivity. For example, phosphoric acid (H₃PO₄) etches aluminum at ~0.1 μm/min in a 1:1 water dilution at 40°C, while nitric acid (HNO₃) increases this to ~1 μm/min. Higher concentrations accelerate etching but may reduce precision due to increased lateral undercutting.

- Time Management: Exposure time directly correlates with depth. In semiconductor processing, silicon is etched with potassium hydroxide (KOH) at 80°C, achieving depths of 50–500 μm over 1–10 minutes. Precision timers, accurate to milliseconds, ensure repeatability, though manual processes may introduce variability (±5%).

- Temperature Regulation: Temperature exponentially affects etch rate via the Arrhenius equation:

R=Aexp{−(Ea/RT)}

where A A A is a pre-exponential factor, Ea E_a Ea is the activation energy, R R R is the gas constant, and T T T is the absolute temperature. For HF etching SiO₂, raising the temperature from 20°C to 40°C doubles the rate from 20 nm/min to 40 nm/min, necessitating thermostats for ±0.1°C control.

- Mask Integrity: Photoresist or hard masks (e.g., Si₃N₄) define the etched area. Mask degradation, such as resist erosion in prolonged HF exposure, increases depth unpredictably. Silicon nitride masks withstand KOH for hours, ensuring depth consistency.

- Endpoint Detection: Visual inspection or chemical indicators signal completion. For instance, etching copper with ferric chloride (FeCl₃) reveals a color shift from metallic to substrate hue, though advanced methods use interferometry to measure depth in real-time with ±1 nm accuracy.

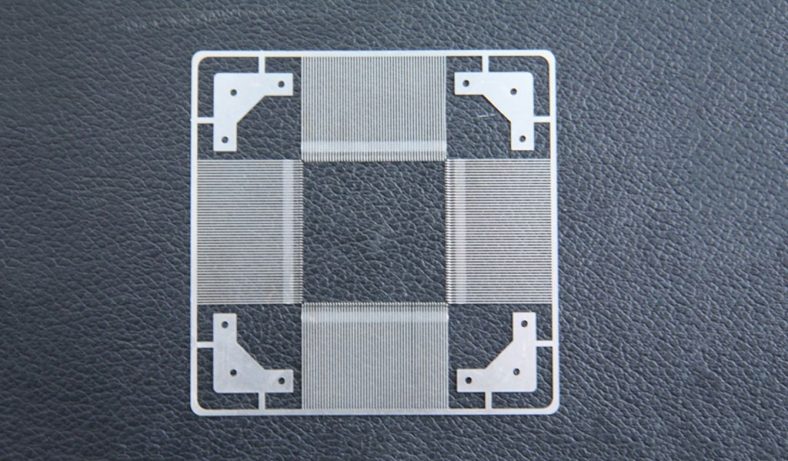

Wet etching’s isotropic nature—etching equally in all directions—limits depth control for fine features, as undercutting widens trenches beyond the mask. Anisotropic wet etching, such as KOH on (100) silicon, exploits crystallographic planes (e.g., slower etching along <111> planes) to achieve V-shaped grooves with depths predictable to within 1 μm over 100 μm.

Dry Etching: Precision Through Plasma and Ions

Dry etching, encompassing plasma-based techniques, offers superior depth control for micro- and nanoscale applications. Reactive ion etching (RIE), inductively coupled plasma (ICP) etching, and deep reactive ion etching (DRIE) dominate semiconductor and MEMS fabrication. Depth control mechanisms include:

- Plasma Parameters: RF power and gas flow rates dictate ion energy and reactive species concentration. In DRIE of silicon using the Bosch process, alternating SF₆ etching (1–3 μm/min) and C₄F₈ passivation cycles achieve depths of 100–500 μm with ±5 nm precision. Power adjustments (e.g., 100 W to 300 W) fine-tune the rate.

- Etch Time and Cycling: The Bosch process controls depth by cycle count, each removing ~1–2 μm. A 100-cycle run at 2 μm/cycle yields 200 μm, monitored by laser interferometry reflecting off the substrate.

- Mask Selectivity: Masks like silicon dioxide or photoresist must resist plasma. SiO₂ withstands SF₆/O₂ plasmas with a selectivity of 100:1 (substrate:mask etch rate), ensuring depth aligns with mask patterns. Selectivity drops with prolonged exposure, requiring recalibration.

- Chamber Conditions: Pressure (1–100 mTorr) affects ion directionality. Lower pressures enhance anisotropy, concentrating etching vertically and reducing lateral deviation, critical for depths below 10 μm.

- Real-Time Monitoring: Reflectance anisotropy spectroscopy (RAS) measures depth in situ by detecting changes in light reflection as layers are removed. For III-V semiconductors like GaAs, RAS achieves ±16 nm accuracy, adjusting etch time dynamically.

Dry etching excels in anisotropy, enabling high-aspect-ratio features (e.g., 20:1 depth-to-width ratios in DRIE), but requires expensive equipment and precise calibration, limiting its use to high-value applications.

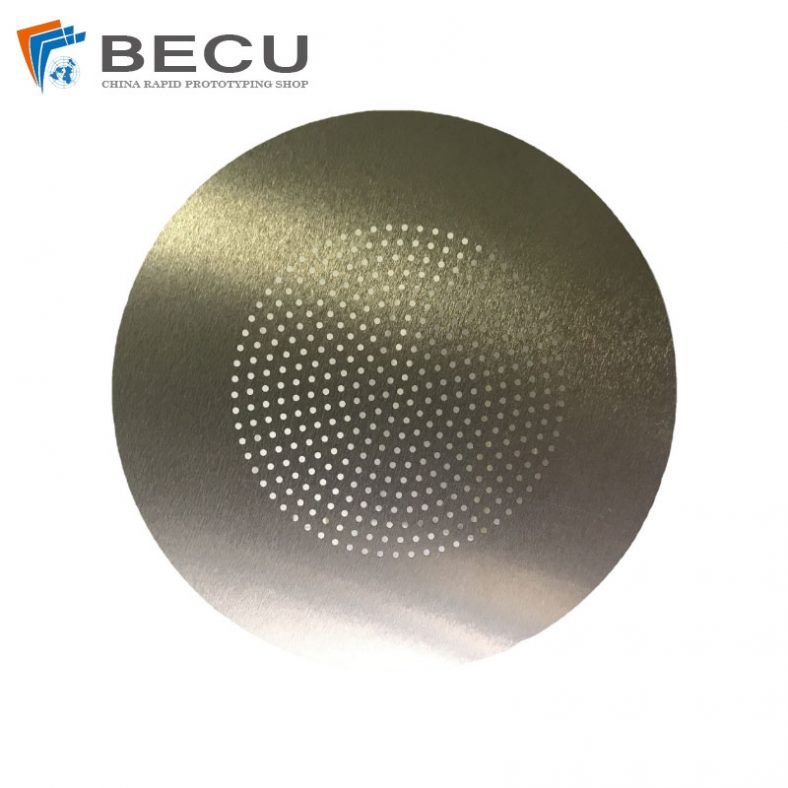

Laser Etching: Ablation-Based Depth Control

Laser etching ablates material via photon energy, offering unparalleled precision for surface structuring. Depth control relies on:

- Pulse Energy: A 1064 nm Nd:YAG laser with 1 mJ pulses removes ~0.5 μm of steel per pulse. Reducing energy to 0.1 mJ limits depth to 50 nm, ideal for thin films.

- Pulse Duration: Femtosecond lasers (10⁻¹⁵ s) minimize heat-affected zones (HAZ), ablating 10–100 nm per pulse in copper, while nanosecond lasers (10⁻⁹ s) deepen HAZ to 1–10 μm, lessening precision.

- Repetition Rate: A 10 Hz laser etches slower (e.g., 1 μm/s) than a 1 kHz laser (1 mm/s), allowing depth increments as fine as 1 nm by adjusting pulse count.

- Focal Precision: Beam focus determines spot size and energy density. A 10 μm spot at 1 J/cm² ablates deeper than a 100 μm spot, with depth controlled to ±5 nm via z-axis positioning.

- Material Properties: Ablation thresholds vary—aluminum (0.1 J/cm²) etches deeper per pulse than titanium (0.5 J/cm²). Calibration curves map pulses to depth, e.g., 100 pulses at 0.2 J/cm² yield 20 μm in aluminum.

Laser etching’s non-contact nature avoids mask wear, but thermal effects in longer pulses can unpredictably deepen etching, requiring ultrashort pulses for nanoscale control.

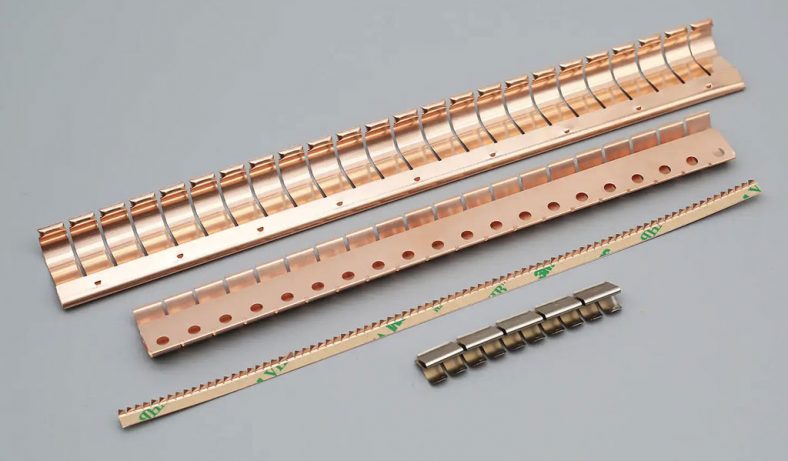

Electrochemical Etching: Voltage-Driven Depth Management

Electrochemical etching, or electropolishing, removes material via anodic dissolution in an electrolyte. Depth control involves:

- Voltage and Current: In stainless steel etching with H₂SO₄-H₃PO₄, 5 V yields 0.1 μm/min, while 10 V increases this to 0.5 μm/min. Constant current (e.g., 1 A/cm²) stabilizes rates.

- Electrolyte Composition: Higher acid concentrations (e.g., 50% H₂SO₄) accelerate etching but reduce uniformity. Additives like glycerol enhance smoothness, aiding depth precision (±10 nm).

- Time Control: A 10-minute etch at 0.2 μm/min yields 2 μm, monitored with digital ammeters for ±1% accuracy.

- Electrode Geometry: Parallel-plate setups ensure uniform fields, minimizing depth variation (<5%) across large areas.

Electrochemical etching excels in smoothing surfaces (e.g., Ra < 10 nm) but struggles with deep features due to diffusion-limited rates.

Monitoring and Feedback Systems

Advanced depth control integrates real-time monitoring:

- Interferometry: Laser interferometers detect thickness changes via interference patterns, achieving ±1 nm resolution in SiO₂ etching.

- RAS: Reflectance shifts indicate layer transitions, controlling GaAs etching to ±16 nm.

- Mass Spectrometry: Plasma etching monitors byproduct ions (e.g., SiF₄), signaling endpoint with ±10 nm precision.

- ** Profilometry**: Post-etch stylus or optical scans verify depth, though not in situ.

These systems adjust parameters dynamically, enhancing reproducibility across batches.

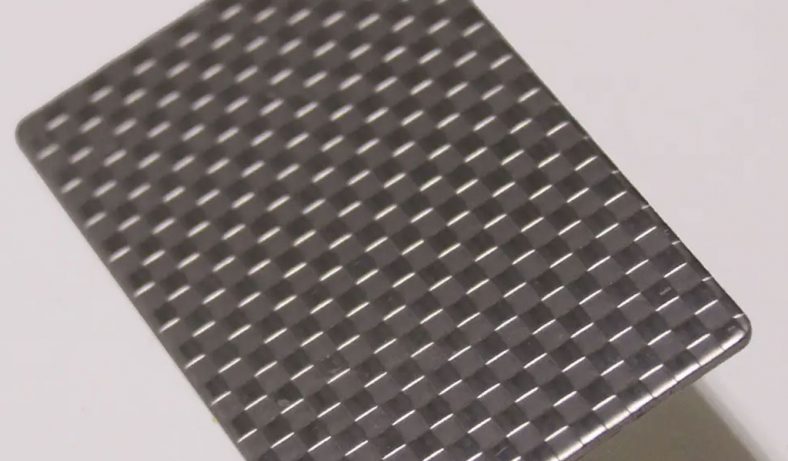

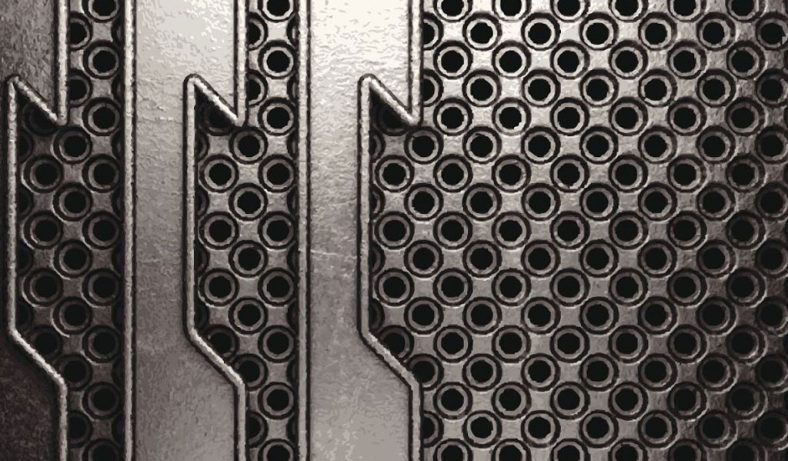

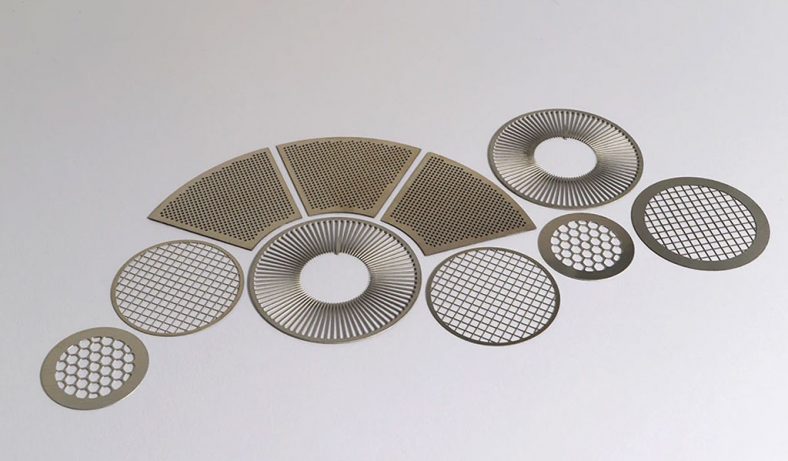

Applications Across Industries

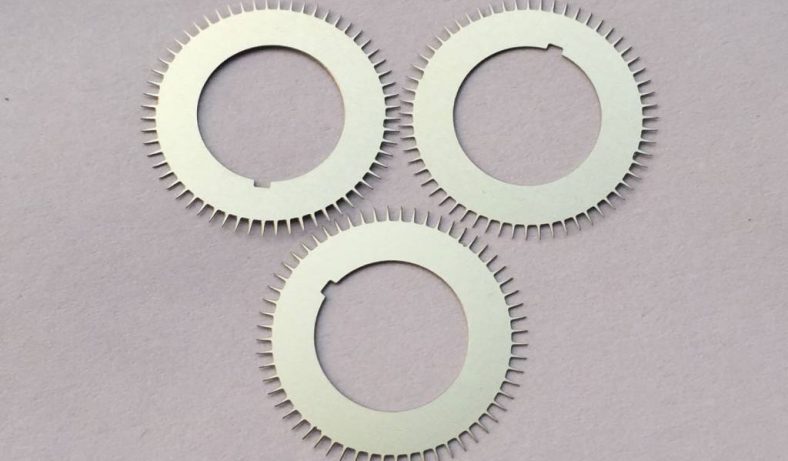

- Semiconductors: DRIE etches 500 μm silicon wafers for MEMS with ±5 nm depth control, critical for accelerometers.

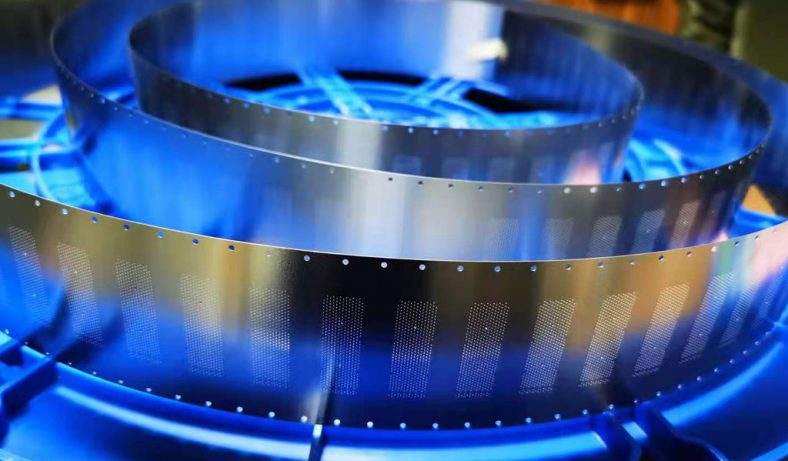

- Aerospace: Wet etching titanium (HF-HNO₃) to 100 μm reduces weight in turbine blades, monitored to ±1 μm.

- Medical Devices: Laser etching stents to 10 μm ensures biocompatibility, controlled to ±5 nm.

- Jewelry: Acid etching silver to 50 μm creates patterns, timed to ±10 μm.

Comparative Table 1: Etching Methods and Depth Control

| Method | Depth Range | Precision (±) | Key Control Parameter | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wet Chemical | 1 μm–1 mm | 1 μm | Etch time, concentration | Cost-effective, simple | Isotropic, undercutting |

| Dry (RIE/DRIE) | 10 nm–500 μm | 5 nm | Plasma power, cycle count | Anisotropic, high precision | Expensive, complex setup |

| Laser | 10 nm–1 mm | 5 nm | Pulse energy, repetition | Non-contact, versatile | Thermal effects in long pulses |

| Electrochemical | 100 nm–100 μm | 10 nm | Voltage, current | Smooth surfaces, uniform | Limited depth, slow rates |

Challenges and Future Directions

Controlling etching depth faces challenges like mask erosion, etchant depletion, and thermal drift. Emerging techniques, such as atomic layer etching (ALE), promise atomic-scale precision (0.1 nm) by cycling adsorption and desorption steps. Machine learning models predict etch rates from historical data, optimizing parameters in real-time. As industries demand finer features, depth control will integrate nanotechnology and AI, pushing precision below 1 nm.

This article, spanning principles to applications, underscores the multifaceted nature of etching depth control, a field where science and engineering converge to shape modern technology.