Laser marking, engraving, and etching are advanced surface modification techniques widely utilized across various industries for creating precise, durable, and aesthetically appealing designs, patterns, or identifiers on materials. These processes leverage the power of focused light energy—typically in the form of lasers—to alter the surface properties of substrates such as metals, plastics, ceramics, glass, and wood. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably in casual conversation, they represent distinct methodologies with unique mechanisms, outcomes, and applications. Understanding the differences between laser marking, engraving, and etching is crucial for selecting the appropriate technique for specific industrial, artistic, or functional purposes.

This article provides a comprehensive examination of laser marking, engraving, and etching, delving into their scientific principles, operational parameters, material interactions, equipment requirements, and practical applications. By exploring these techniques in detail, we aim to elucidate their individual strengths and limitations, offering a thorough resource for engineers, designers, researchers, and hobbyists alike.

Fundamental Principles of Laser-Based Surface Modification

Lasers (Light Amplification by Stimulated Emission of Radiation) are monochromatic, coherent light sources capable of delivering concentrated energy to a precise location on a material’s surface. The interaction between the laser beam and the substrate dictates the outcome of the process, whether it be marking, engraving, or etching. The primary factors influencing this interaction include laser wavelength, power intensity, pulse duration, and the material’s physical and chemical properties, such as reflectivity, thermal conductivity, and melting point.

Laser Marking: Surface Alteration Without Material Removal

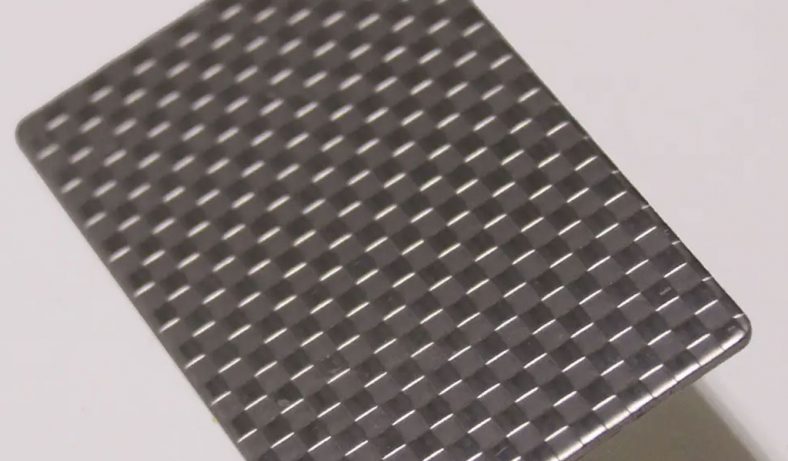

Laser marking involves altering the surface of a material to create visible patterns, text, or codes without significantly removing material. This technique typically modifies the surface’s color, texture, or reflectivity through processes such as oxidation, annealing, foaming, or carbonization. The laser beam interacts with the material at a superficial level, often penetrating only a few micrometers into the surface.

For instance, in metal marking, a low-power laser may heat the surface to induce oxide layer formation, resulting in a high-contrast mark. In plastics, the laser may cause localized melting or chemical changes, such as carbonization, to produce dark markings. The absence of material removal makes laser marking a non-invasive technique, preserving the structural integrity of the workpiece.

Laser Engraving: Material Removal Through Vaporization

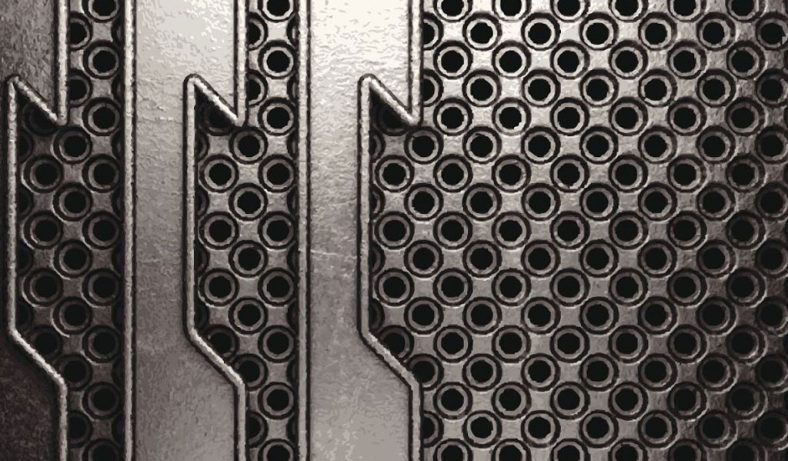

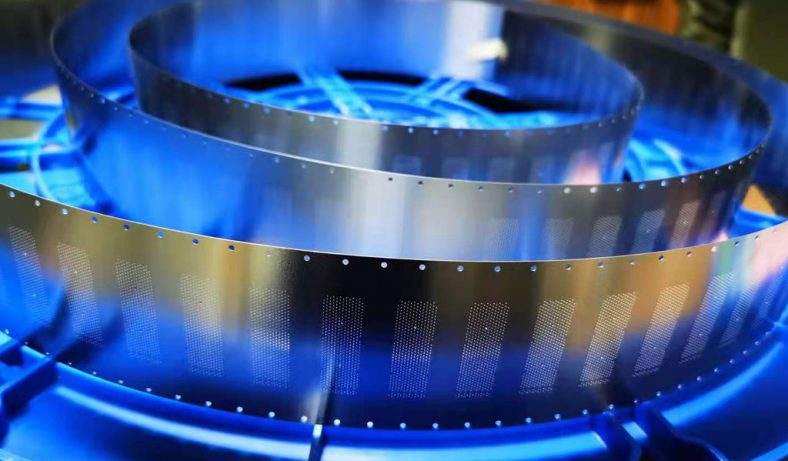

Laser engraving, in contrast, is a subtractive process that removes material from the surface to create a recessed design. The laser beam, operating at higher power levels, vaporizes the material by converting it into gas or plasma. This results in a cavity or depression, typically ranging from tens of micrometers to several millimeters in depth, depending on the laser settings and material properties.

Engraving is achieved by focusing a high-energy laser beam onto the surface, causing rapid heating and material ablation. The depth and width of the engraved feature are controlled by parameters such as laser power, scanning speed, and the number of passes. This technique is particularly effective for creating tactile, three-dimensional designs on materials like wood, metal, and acrylic.

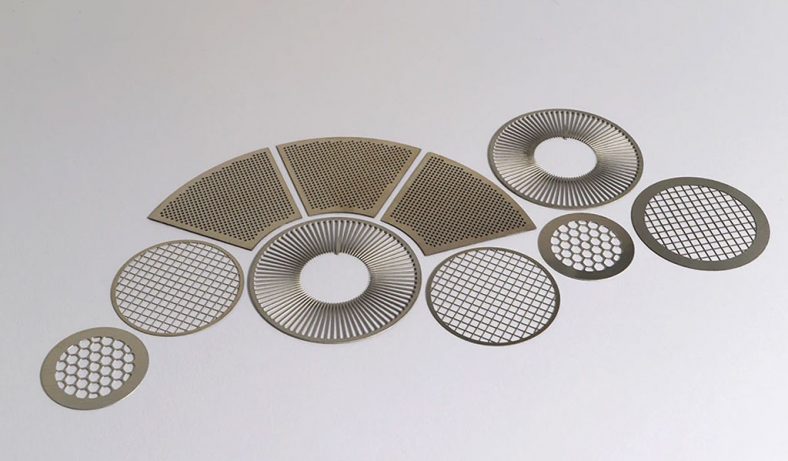

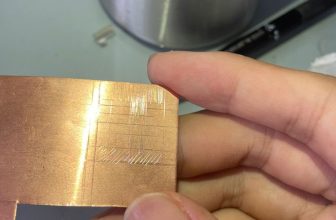

Laser Etching: Controlled Material Removal and Surface Texturing

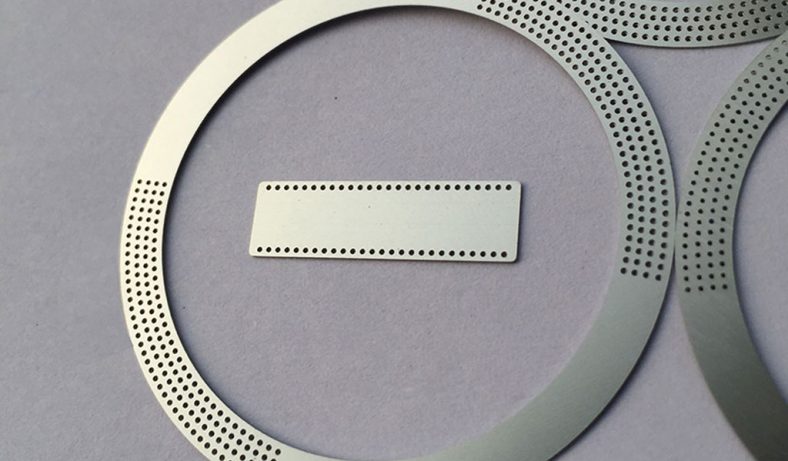

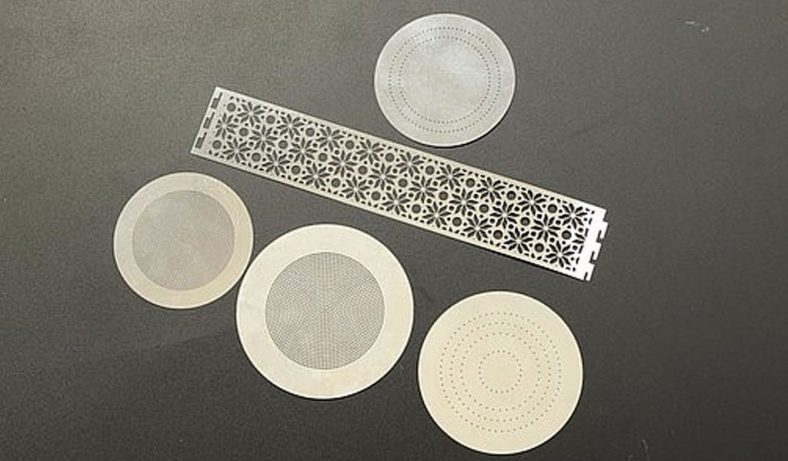

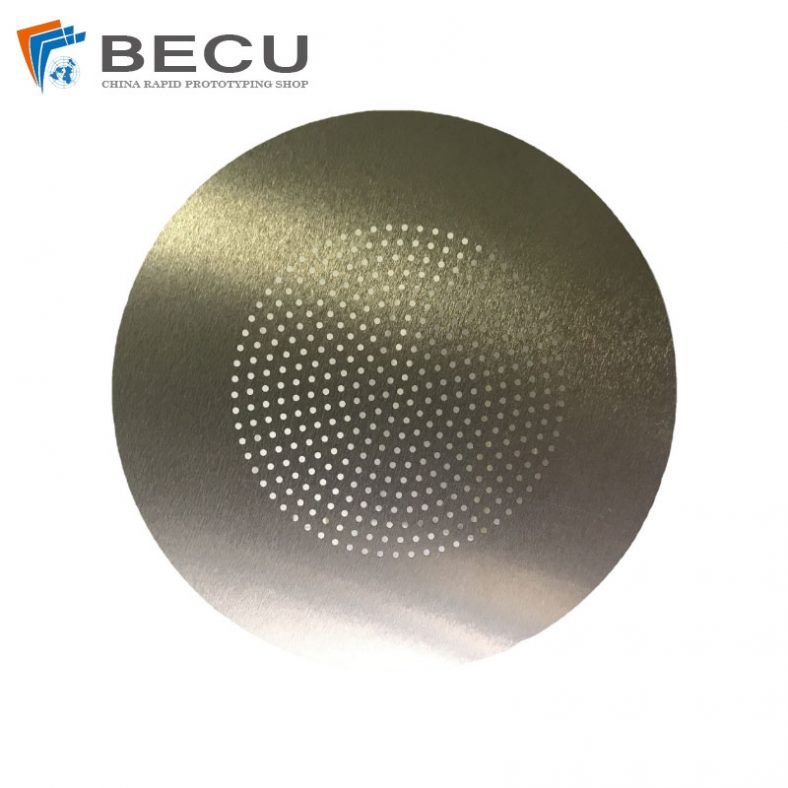

Laser etching is often considered a subset of engraving but is distinguished by its emphasis on shallow material removal and surface texturing. Etching typically removes a thin layer of material—often less than 0.001 inches (25.4 micrometers)—to produce fine, detailed patterns or textures. The process relies on the laser’s ability to melt or ablate a controlled amount of material, leaving behind a slightly recessed mark.

Etching is frequently used to enhance surface properties, such as improving adhesion for coatings or creating micro-patterns for aesthetic purposes. While similar to engraving in its subtractive nature, etching is generally less aggressive, focusing on precision rather than depth.

Physics and Chemistry of Laser-Material Interactions

The efficacy of laser marking, engraving, and etching depends on the complex interplay between the laser beam and the material’s physical and chemical characteristics. Below, we explore the key mechanisms involved in each process.

Laser Marking Mechanisms

Laser marking employs several distinct mechanisms depending on the material:

- Oxidation/Annealing: On metals like stainless steel or titanium, the laser heats the surface in the presence of oxygen, forming a thin oxide layer. This layer alters the material’s reflectivity, creating a contrasting mark without material loss. Annealing, a related process, involves heating the metal below its melting point to induce microstructural changes, resulting in color shifts (e.g., black, blue, or red marks on steel).

- Foaming: In plastics, the laser causes localized gas release, forming bubbles that scatter light and produce a light-colored mark. This is common in polymers like ABS or PVC.

- Carbonization: Organic materials (e.g., wood, leather) or certain plastics undergo thermal decomposition, leaving a dark, carbon-rich residue on the surface.

- Bleaching: In dyed or coated materials, the laser removes or alters pigments, creating a lighter mark against a darker background.

These processes are non-abrasive and typically operate at lower energy levels (e.g., 10-50 watts for fiber lasers), ensuring minimal thermal damage to surrounding areas.

Laser Engraving Mechanisms

Engraving relies on ablation, where the laser delivers sufficient energy to exceed the material’s vaporization threshold. The absorbed energy rapidly heats the surface, converting solid material into gas or plasma. This process generates debris (e.g., vapor, soot, or particulates), necessitating proper ventilation or extraction systems in industrial settings.

The depth of engraving is governed by the laser’s energy density (measured in joules per square centimeter) and the material’s ablation threshold. For example, metals like aluminum require higher power (e.g., 50-100 watts) due to their high thermal conductivity, while softer materials like wood engrave effectively at lower settings (e.g., 20-40 watts).

Laser Etching Mechanisms

Etching combines elements of ablation and melting. The laser removes a thin layer of material while simultaneously altering the surface texture. For instance, on metals, the laser may melt a shallow layer, which then resolidifies into a textured pattern. In glass, etching often involves micro-fracturing the surface to create a frosted appearance.

Etching typically uses pulsed lasers with short pulse durations (e.g., nanoseconds or picoseconds) to achieve high precision and minimize heat-affected zones (HAZ). The shallow nature of etching distinguishes it from deeper engraving processes.

Equipment and Technology

The choice of laser system significantly impacts the quality and efficiency of marking, engraving, and etching. Common laser types include fiber lasers, CO2 lasers, and Nd:YAG lasers, each suited to specific materials and applications.

Laser Types and Their Applications

- Fiber Lasers:

- Wavelength: ~1,064 nm

- Best for: Metals, some plastics

- Applications: Marking (e.g., barcodes on steel), engraving (e.g., serial numbers on aluminum), etching (e.g., micro-texturing on titanium)

- Advantages: High beam quality, long lifespan, energy efficiency

- CO2 Lasers:

- Wavelength: ~10,600 nm

- Best for: Non-metals (wood, glass, acrylic, leather)

- Applications: Engraving (e.g., wooden plaques), marking (e.g., leather tags), etching (e.g., glass frosting)

- Advantages: Versatile, cost-effective for organic materials

- Nd:YAG Lasers:

- Wavelength: ~1,064 nm

- Best for: Metals, ceramics

- Applications: Deep engraving (e.g., molds), high-contrast marking (e.g., medical devices)

- Advantages: High peak power, suitable for reflective surfaces

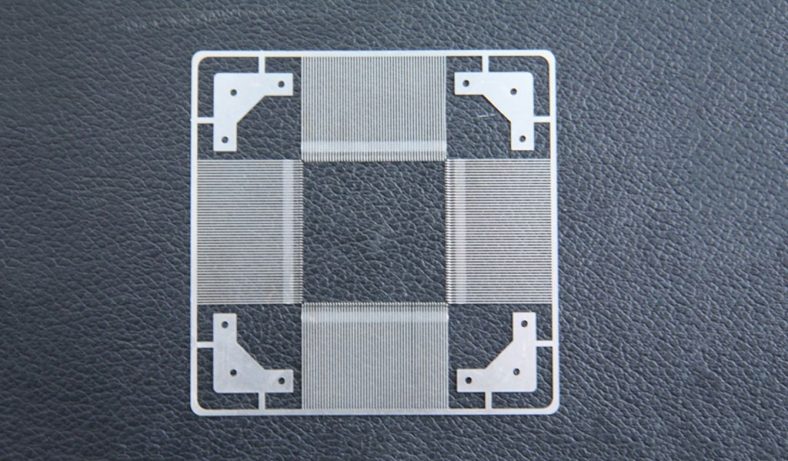

System Components

- Laser Source: Generates the beam; power ranges from 10 watts (marking) to over 100 watts (engraving).

- Galvanometer Scanners: Direct the beam with precision using mirrors, enabling rapid pattern creation.

- Focusing Optics: Concentrate the beam to a spot size as small as 20 micrometers for detailed work.

- Control Software: Translates digital designs (e.g., CAD files) into laser movements, adjusting parameters like speed and power.

Comparative Analysis of Techniques

To provide a clearer understanding, the following table compares laser marking, engraving, and etching across key parameters:

| Parameter | Laser Marking | Laser Engraving | Laser Etching |

|---|---|---|---|

| Depth of Effect | <0.01 mm (superficial) | 0.05-5 mm (variable) | <0.025 mm (shallow) |

| Material Removal | No | Yes (vaporization) | Yes (minimal) |

| Primary Mechanism | Color change, oxidation, foaming | Ablation | Ablation + texturing |

| Laser Power | Low (10-50 W) | Medium-High (20-100+ W) | Low-Medium (10-50 W) |

| Speed | Fast (e.g., 1000 mm/s) | Moderate (e.g., 500 mm/s) | Fast (e.g., 800 mm/s) |

| Applications | Barcodes, logos, serial numbers | 3D designs, molds, jewelry | Surface prep, fine patterns, glass art |

| Material Suitability | Metals, plastics, ceramics | Metals, wood, acrylic | Metals, glass, polymers |

| Precision | High | Moderate | Very High |

| Durability of Mark | Excellent (resistant to wear) | Excellent (deep and permanent) | Good (shallow but durable) |

Applications Across Industries

Industrial Manufacturing

- Laser Marking: Used for traceability in automotive and aerospace industries, e.g., VIN numbers on car parts or QR codes on aircraft components. Its non-contact nature ensures no mechanical stress on delicate parts.

- Laser Engraving: Employed to create molds, dies, and tooling with intricate designs. For example, engraved steel molds are used in injection molding for mass production.

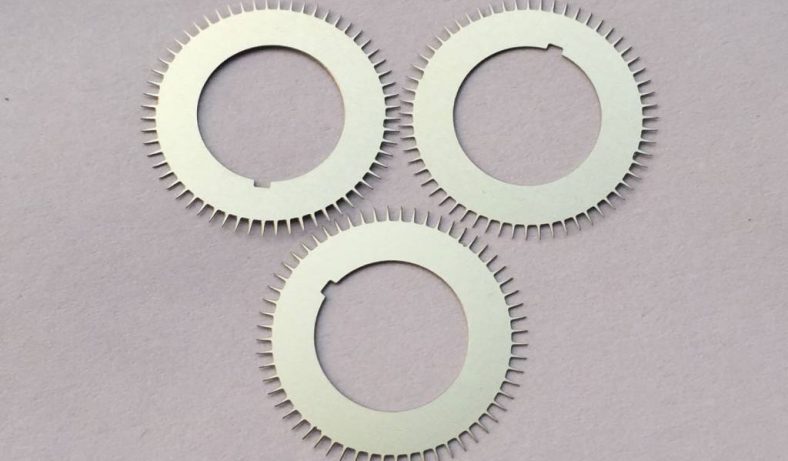

- Laser Etching: Prepares surfaces for bonding or coating, such as etching titanium aerospace components to improve paint adhesion.

Medical Devices

- Laser Marking: Marks surgical instruments and implants (e.g., stainless steel scalpels) with identification codes that withstand sterilization processes.

- Laser Engraving: Creates custom prosthetics or dental implants with patient-specific designs.

- Laser Etching: Textures medical-grade polymers or ceramics for enhanced biocompatibility.

Jewelry and Art

- Laser Marking: Adds hallmarks or logos to precious metals like gold and silver without compromising their value.

- Laser Engraving: Carves intricate 3D patterns into rings, pendants, or wooden sculptures.

- Laser Etching: Produces delicate designs on glass or gemstones, such as frosted patterns on crystal.

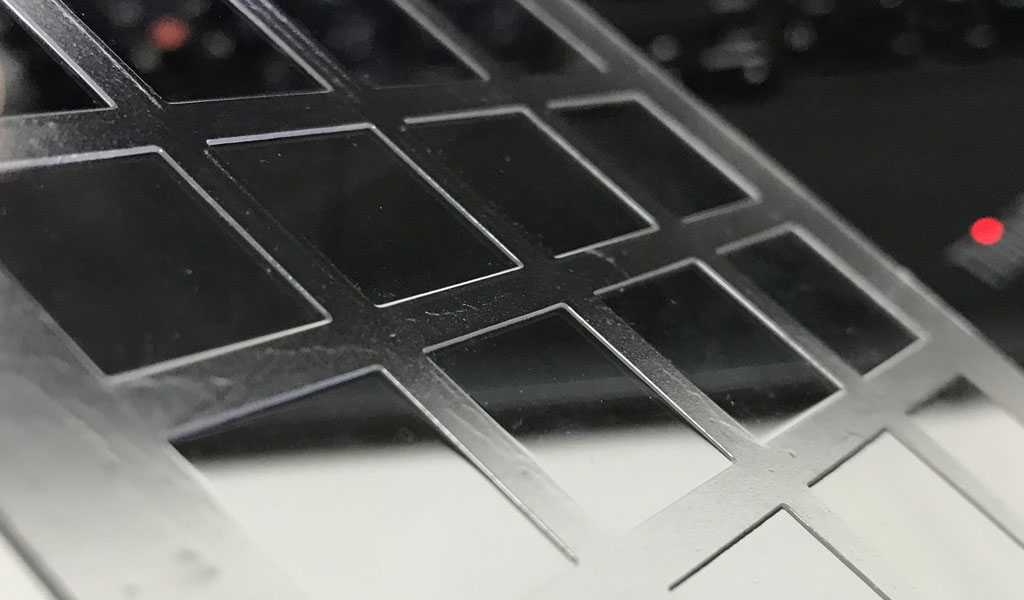

Electronics

- Laser Marking: Labels circuit boards and microchips with serial numbers or brand identifiers.

- Laser Engraving: Cuts precise channels or shapes in semiconductor materials.

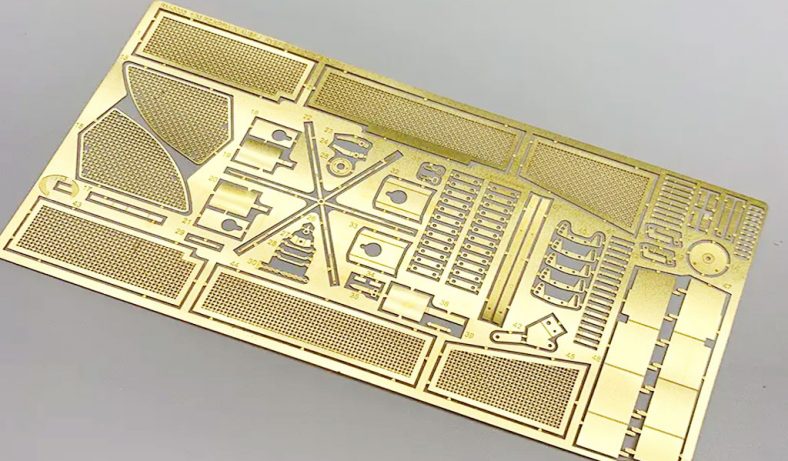

- Laser Etching: Creates micro-patterns on silicon wafers for improved electrical performance.

Advantages and Limitations

Laser Marking

- Advantages: Fast, non-contact, versatile, minimal material damage, high contrast.

- Limitations: Limited to surface effects; not suitable for deep designs.

Laser Engraving

- Advantages: Deep, permanent results; ideal for tactile or structural modifications.

- Limitations: Slower, produces debris, higher energy consumption.

Laser Etching

- Advantages: High precision, minimal material removal, excellent for fine details.

- Limitations: Shallow marks may wear over time in high-abrasion environments.

Material-Specific Considerations

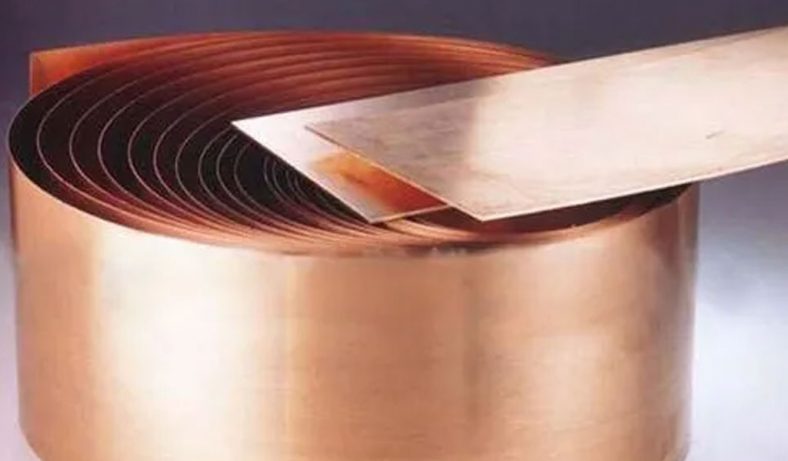

Metals

- Marking: Annealing works well on stainless steel; foaming is ineffective.

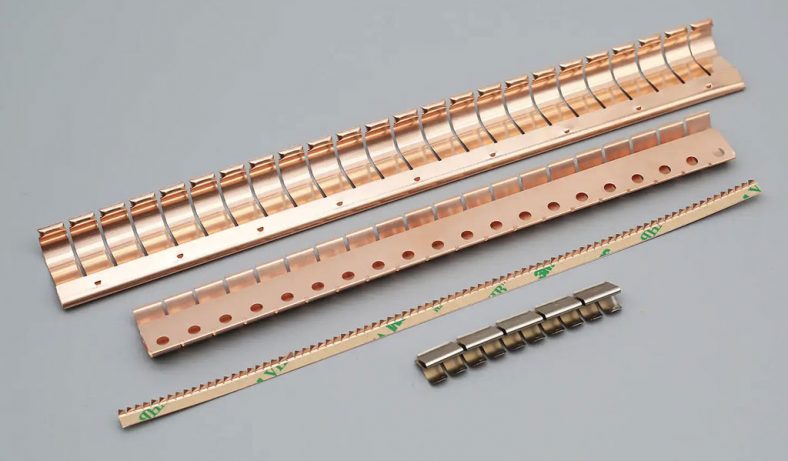

- Engraving: High-power fiber lasers excel on aluminum and brass.

- Etching: Pulsed lasers create micro-textures on titanium.

Plastics

- Marking: Foaming and carbonization are common; results vary by polymer type.

- Engraving: CO2 lasers cut deep into acrylic or PVC.

- Etching: Shallow marks enhance aesthetics on ABS or polycarbonate.

Wood and Organics

- Marking: Carbonization produces dark marks on wood or leather.

- Engraving: CO2 lasers carve detailed reliefs in hardwood.

- Etching: Limited use; shallow patterns may suffice for decorative purposes.

Glass and Ceramics

- Marking: Rarely used; color change is difficult to achieve.

- Engraving: Deep cuts are possible but risk cracking.

- Etching: Ideal for frosting or micro-fracturing glass surfaces.

Conclusion

Laser processes are generally eco-friendly compared to chemical etching or mechanical engraving, as they produce no liquid waste and require no consumables like inks or acids. However, engraving and etching generate fumes and particulates, necessitating robust ventilation systems. Safety protocols include eye protection (e.g., laser-specific goggles) and enclosed workspaces to prevent accidental exposure to laser radiation.

Advancements in laser technology, such as ultrafast lasers (e.g., femtosecond lasers), promise greater precision and reduced thermal damage, particularly for etching and marking. Integration with artificial intelligence and automation is enhancing process efficiency, enabling real-time adjustments to laser parameters based on material feedback. Additionally, hybrid systems combining marking, engraving, and etching capabilities are emerging, offering versatile solutions for complex manufacturing needs.

Laser marking, engraving, and etching represent a spectrum of laser-based techniques tailored to diverse applications. Marking excels in superficial, high-speed identification; engraving provides deep, durable designs; and etching offers precision for fine texturing. By understanding their differences—rooted in physics, equipment, and material interactions—users can optimize their choice of technique, balancing factors like speed, depth, and cost. As laser technology continues to evolve, these methods will play an increasingly vital role in shaping the future of manufacturing, art, and innovation.