In the realm of manufacturing, a die is a specialized tool used to shape, cut, or form materials—typically metals, plastics, or composites—into specific geometries through processes such as stamping, forging, extrusion, or casting. Dies are fundamental to mass production, enabling the consistent replication of parts with high precision and efficiency. The term “die” originates from the Latin datum, meaning “given,” reflecting its role in imparting a predetermined form to a workpiece. This article explores the multifaceted nature of dies in manufacturing, delving into their types, design principles, materials, applications, and technological advancements, while providing a comprehensive scientific analysis supported by detailed comparative tables.

Historical Context and Evolution

The use of dies dates back to antiquity, with early examples found in coin minting during the 7th century BCE in Lydia (modern-day Turkey). These rudimentary dies, often carved from stone or bronze, were struck manually to imprint designs onto metal blanks. The Industrial Revolution in the 18th century marked a turning point, as mechanized presses and steam power necessitated more durable and precise dies made from iron and steel. By the 20th century, the advent of computer-aided design (CAD) and computer numerical control (CNC) machining revolutionized die production, enabling complex geometries and tighter tolerances. Today, dies are integral to industries ranging from automotive and aerospace to electronics and packaging, reflecting centuries of technological refinement.

Fundamental Principles of Dies

At its core, a die operates by applying force to a workpiece, either through cutting (shearing) or forming (plastic deformation). The process involves a die cavity or surface that defines the final shape of the part, often paired with a complementary tool, such as a punch in stamping or a hammer in forging. The workpiece, typically a sheet, billet, or molten material, undergoes controlled deformation or separation based on the die’s geometry. Key mechanical principles governing die operation include stress, strain, and material flow, which are influenced by factors such as material properties, temperature, and lubrication.

Dies are classified broadly into two categories: cutting dies and forming dies. Cutting dies sever material, as seen in blanking or trimming operations, while forming dies reshape material without removing it, as in bending, drawing, or extruding. Hybrid dies, such as progressive or compound dies, combine these functions to perform multiple operations in a single stroke, enhancing efficiency in high-volume production.

Types of Dies

The diversity of manufacturing processes has led to a wide array of die types, each tailored to specific applications. Below is an exhaustive exploration of the primary die categories, their mechanisms, and their industrial significance.

1. Stamping Dies

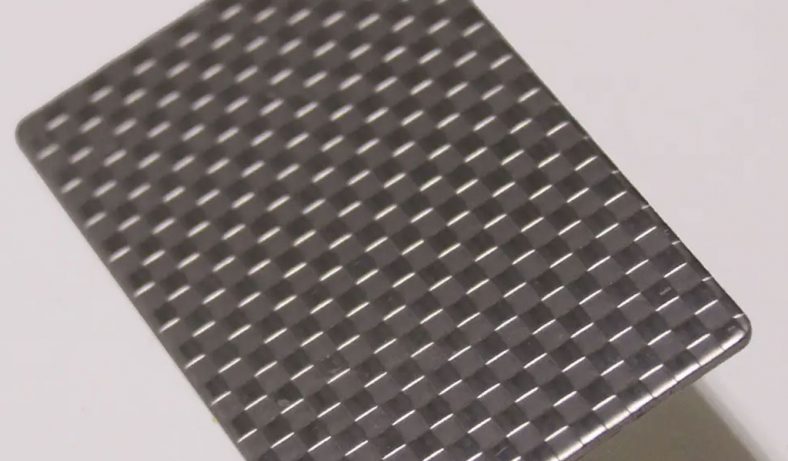

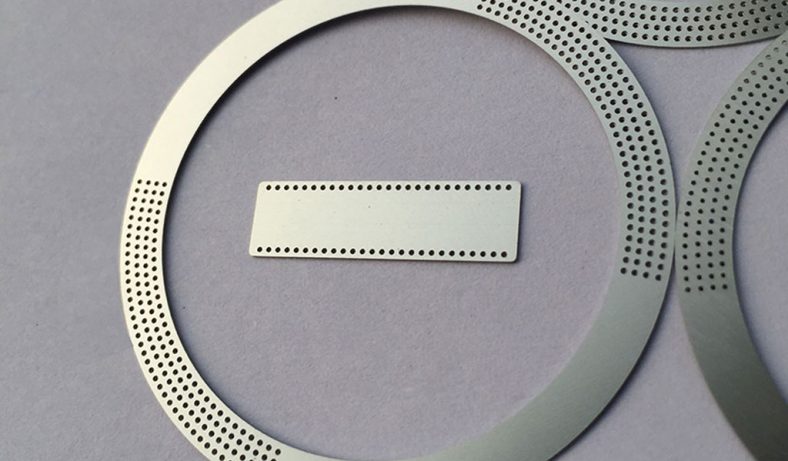

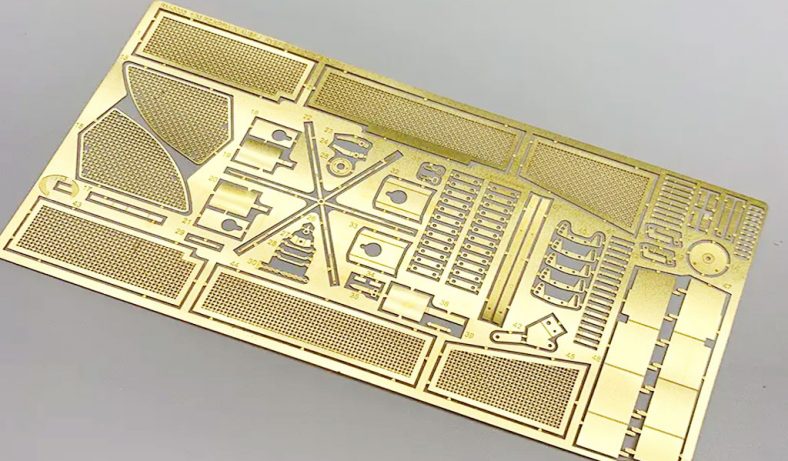

Stamping dies are used in sheet metal forming to cut or shape flat metal blanks into finished parts. Common subtypes include:

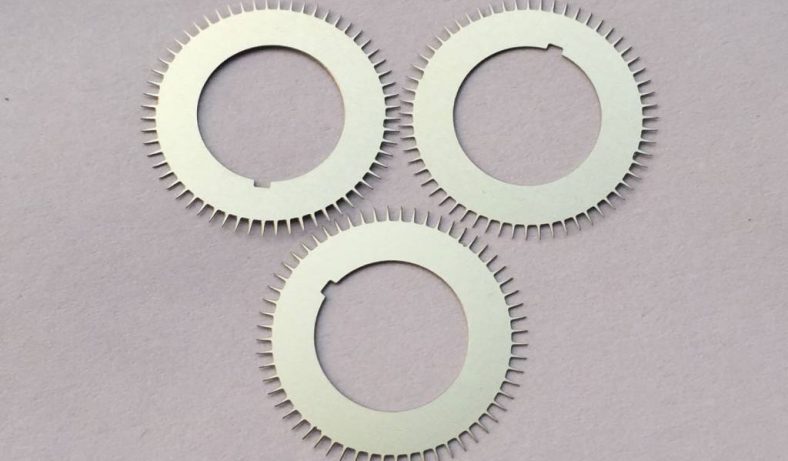

- Blanking Dies: These remove a piece (blank) from a larger sheet, often the first step in part production. The blanking process relies on shear forces exceeding the material’s ultimate tensile strength.

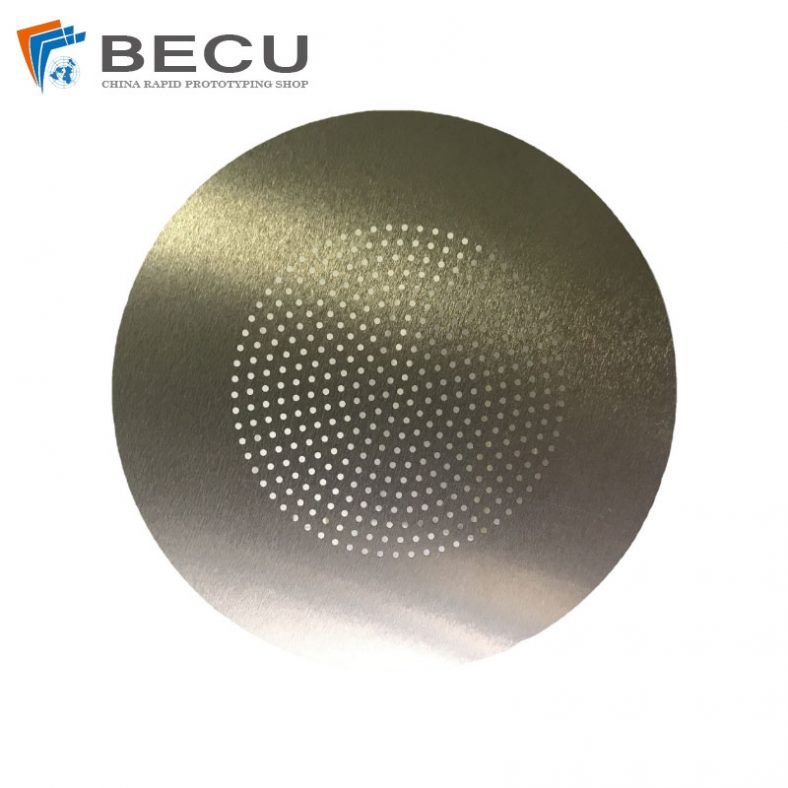

- Piercing Dies: These punch holes or apertures into a workpiece, differing from blanking in that the removed material (slug) is scrap.

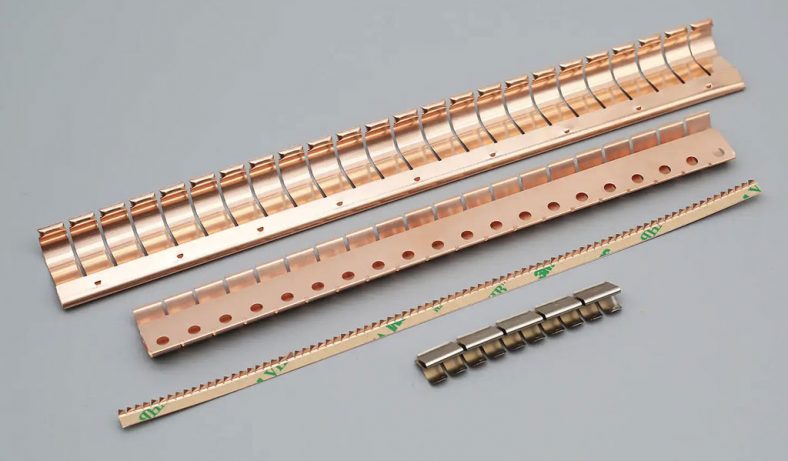

- Bending Dies: These impart angular deformation to a sheet, typically using a V-shaped or U-shaped cavity.

- Drawing Dies: These stretch a blank into a deeper, hollow shape, such as a cup or can, by controlling material flow under tensile stress.

Stamping dies are widely employed in the automotive industry for producing body panels, brackets, and chassis components. Their design requires precision to minimize burrs and ensure dimensional accuracy.

2. Forging Dies

Forging dies shape metal through compressive forces, often at elevated temperatures. They are categorized as:

- Open-Die Forging: Involves simple dies with flat or contoured surfaces, allowing material to flow freely. Used for large, low-precision parts like shafts or rings.

- Closed-Die Forging (Impression-Die Forging): Employs a cavity that fully encloses the workpiece, producing complex shapes with high accuracy, such as gears or connecting rods.

Forging dies must withstand extreme pressures (up to 1000 MPa) and thermal cycling, necessitating robust materials like tool steels or carbide alloys.

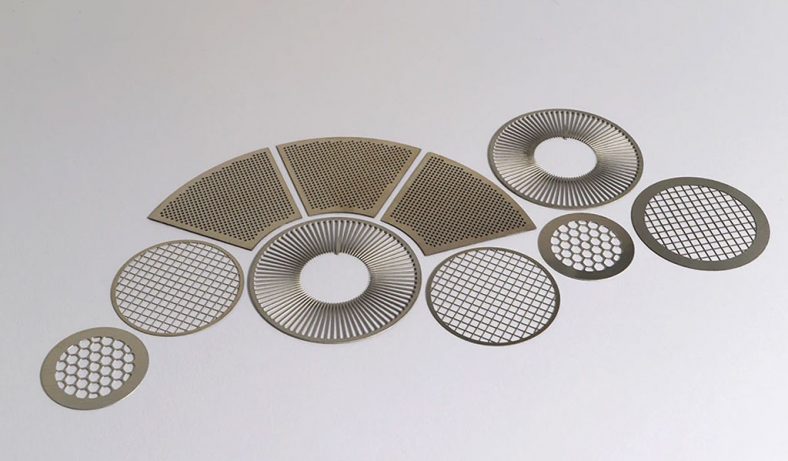

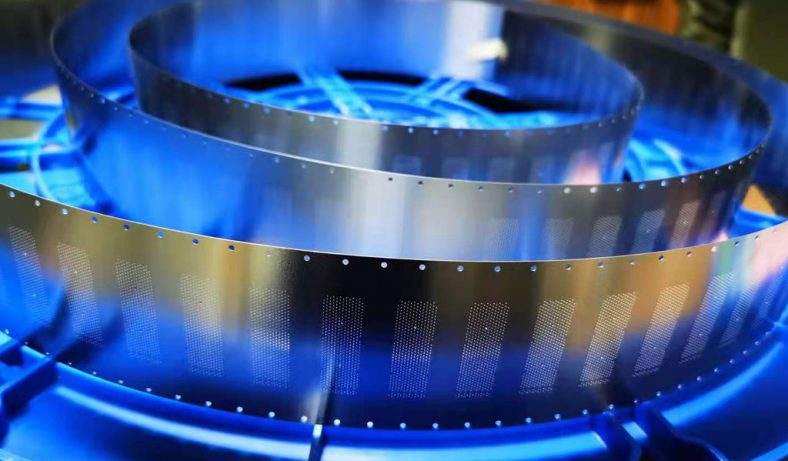

3. Extrusion Dies

Extrusion dies force material—typically metal or plastic—through a shaped orifice to create continuous profiles, such as pipes, rods, or channels. The die’s cross-sectional design dictates the final shape, while factors like extrusion ratio, temperature, and speed influence material flow and surface finish. Aluminum window frames and plastic tubing are common products of extrusion dies.

4. Casting Dies

In die casting, molten metal is injected into a die under high pressure (10–200 MPa) to form intricate parts with fine surface detail. These dies, often made of steel, consist of two halves: a stationary cover die and a movable ejector die. Applications include engine blocks, toy figurines, and electronic housings. The process demands precise cooling channels to manage solidification and prevent defects like porosity.

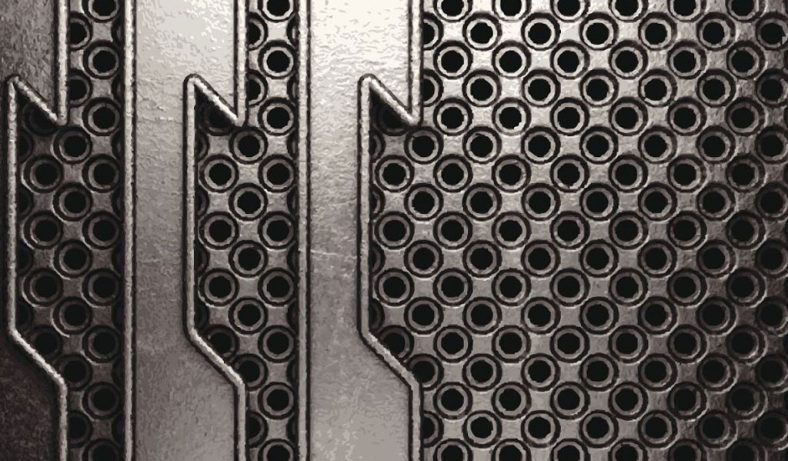

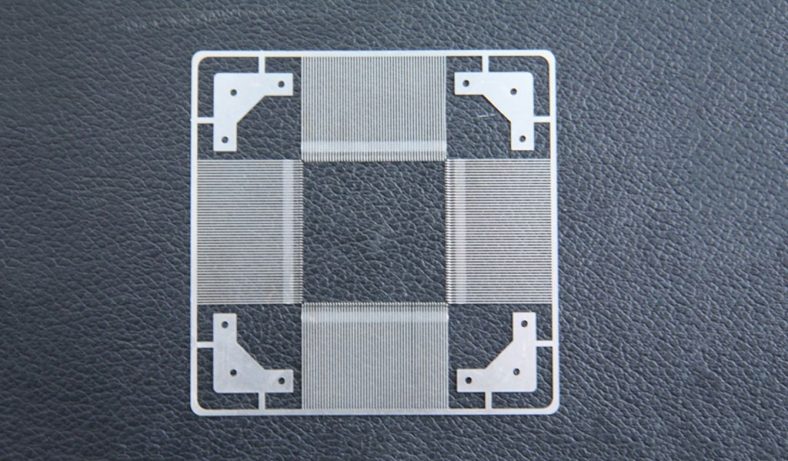

5. Progressive and Compound Dies

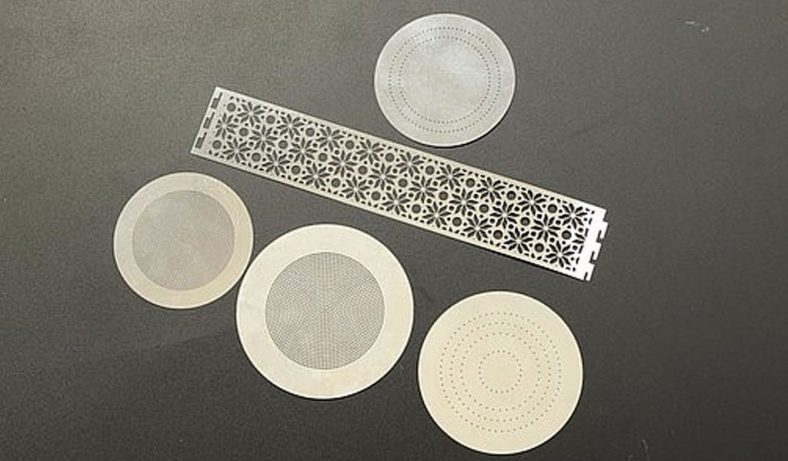

- Progressive Dies: These perform sequential operations (e.g., blanking, piercing, bending) as the workpiece moves through multiple stations in a single die set. They are ideal for high-speed production of small, complex parts like electrical connectors.

- Compound Dies: These execute multiple operations (e.g., blanking and piercing) in a single stroke, offering high precision for flat parts like washers.

Die Materials

The performance and longevity of a die hinge on its material properties, which must balance hardness, toughness, wear resistance, and thermal stability. Common materials include:

- Tool Steels: Such as AISI D2 or H13, offering high hardness (up to 60 HRC) and wear resistance for stamping and forging dies.

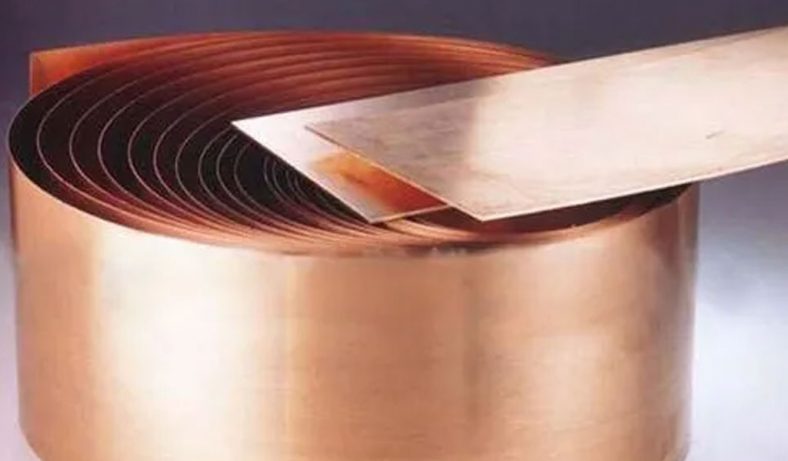

- Carbides: Tungsten carbide or cobalt-bonded carbide, used in high-wear applications like wire drawing or extrusion, with hardness exceeding 70 HRC.

- High-Speed Steels (HSS): Like M2 or T1, suited for cutting dies due to their ability to retain hardness at elevated temperatures.

- Ceramics: Emerging in niche applications, ceramics like silicon nitride provide extreme wear resistance and thermal insulation for specialized dies.

Material selection depends on the workpiece material, process conditions, and production volume. For instance, softer aluminum workpieces may require less abrasive-resistant dies than hardened steels.

Design and Fabrication of Dies

Die design is a multidisciplinary endeavor, integrating mechanical engineering, materials science, and computational modeling. Key considerations include:

- Clearance: The gap between the punch and die, typically 5–10% of material thickness, affects edge quality and tool life.

- Tolerances: Precision to within ±0.01 mm ensures part consistency.

- Draft Angles: Slight tapers (1–5°) facilitate part ejection in forming dies.

- Surface Finish: Polished surfaces reduce friction and improve material flow.

Modern dies are designed using CAD software, with finite element analysis (FEA) simulating stress distribution and material behavior. Fabrication involves CNC machining, electrical discharge machining (EDM), or additive manufacturing for complex geometries. Heat treatment, such as quenching and tempering, enhances durability, while coatings like titanium nitride (TiN) or diamond-like carbon (DLC) extend wear life.

Applications Across Industries

Dies underpin modern manufacturing across diverse sectors:

- Automotive: Stamping dies produce fenders, hoods, and structural components, while forging dies craft crankshafts and axles.

- Aerospace: Precision casting dies form turbine blades and lightweight alloy parts.

- Electronics: Progressive dies manufacture connectors, heat sinks, and enclosures.

- Packaging: Drawing dies shape aluminum cans and foil containers.

- Medical: Extrusion dies create tubing, and stamping dies produce surgical instruments.

Comparative Analysis of Die Types

The following tables provide a detailed comparison of die types based on key parameters, enhancing the scientific rigor of this discussion.

Table 1: Mechanical and Operational Characteristics of Dies

| Die Type | Process Type | Force Applied (MPa) | Material Suitability | Precision (mm) | Production Rate (parts/min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blanking Die | Cutting | 50–500 | Sheet metals (steel, Al) | ±0.05 | 50–200 |

| Drawing Die | Forming | 100–800 | Ductile metals (Cu, Al) | ±0.02 | 20–100 |

| Forging Die (Closed) | Forming | 500–1000 | Steel, Ti, alloys | ±0.1 | 5–50 |

| Extrusion Die | Forming | 50–300 | Al, plastics, Cu | ±0.05 | Continuous (m/min) |

| Die Casting Die | Casting | 10–200 | Zn, Al, Mg | ±0.01 | 10–60 |

| Progressive Die | Cutting/Forming | 50–600 | Sheet metals | ±0.03 | 100–500 |

Table 2: Material and Durability Comparison

| Die Material | Hardness (HRC) | Wear Resistance | Thermal Stability (°C) | Cost ($/kg) | Typical Lifespan (cycles) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tool Steel (D2) | 58–62 | High | 400–500 | 10–20 | 100,000–500,000 |

| Tungsten Carbide | 70–90 | Very High | 800–1000 | 50–100 | 1,000,000+ |

| High-Speed Steel | 60–65 | High | 550–600 | 15–30 | 200,000–800,000 |

| Ceramic (Si3N4) | 80–90 | Extreme | 1200–1500 | 100–200 | 500,000–2,000,000 |

Table 3: Industry-Specific Applications

| Industry | Dominant Die Type | Typical Parts Produced | Material Used | Cycle Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Automotive | Stamping/Forging | Panels, gears, shafts | Steel, Al | 1–10 |

| Aerospace | Casting/Forging | Blades, structural components | Ti, Al alloys | 10–60 |

| Electronics | Progressive | Connectors, housings | Cu, brass | 0.1–2 |

| Packaging | Drawing | Cans, containers | Al, tinplate | 0.5–5 |

Technological Advancements

Recent innovations have transformed die manufacturing:

- Additive Manufacturing: 3D printing enables rapid prototyping and complex internal cooling channels in casting dies.

- Smart Dies: Embedded sensors monitor pressure, temperature, and wear in real time, optimizing maintenance schedules.

- Nanotechnology: Nano-coatings enhance surface hardness and reduce friction, extending die life by up to 50%.

- Simulation Tools: Advanced FEA and computational fluid dynamics (CFD) predict material flow and die failure, reducing trial-and-error costs.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their versatility, dies face challenges:

- Wear and Fatigue: Repeated loading causes microcracks and surface degradation, necessitating frequent maintenance or replacement.

- Cost: High initial investment in design and fabrication limits use in low-volume production.

- Material Constraints: Dies must be compatible with workpiece properties, restricting flexibility.

- Thermal Effects: In hot processes like forging or casting, thermal expansion and contraction can distort die geometry.

Conclusion

The future of dies in manufacturing lies in sustainability and automation. Research focuses on:

- Eco-Friendly Materials: Biodegradable composites and recycled alloys for die production.

- AI Integration: Machine learning algorithms to optimize die design and predict failure.

- Modular Dies: Interchangeable components to adapt to varying part geometries, reducing costs.

Dies are the backbone of modern manufacturing, embodying a synergy of engineering precision and material science. From ancient coin minting to contemporary aerospace components, their evolution mirrors humanity’s technological progress. As industries demand greater efficiency and sustainability, dies will continue to adapt, driven by innovations in materials, design, and digital integration. This comprehensive analysis, supported by detailed tables, underscores their scientific and industrial significance, offering a foundation for further exploration in this dynamic field.